By Vincent Stanton, Jr.

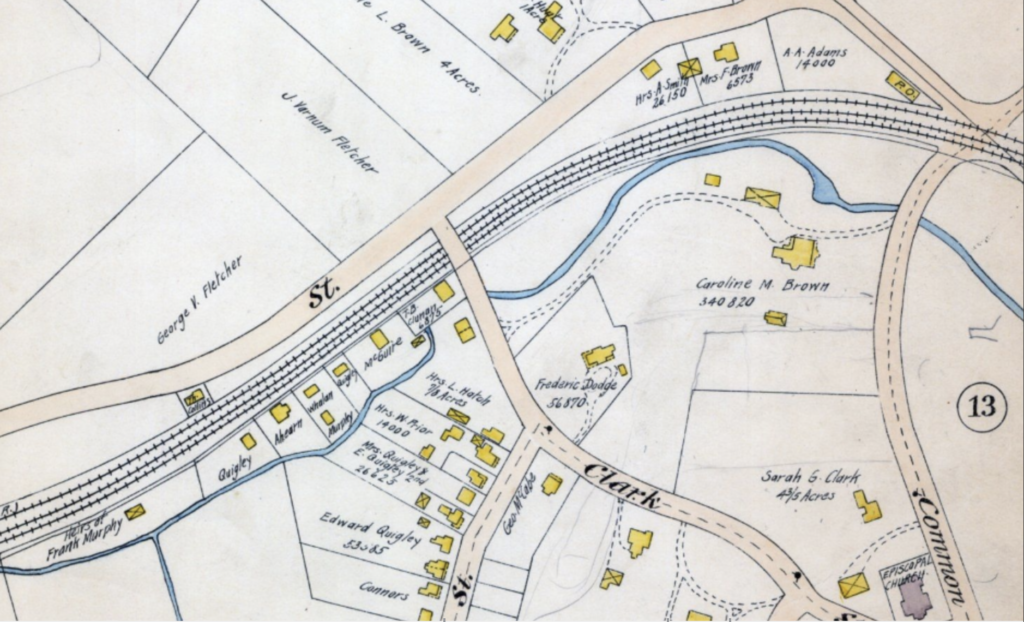

In 1844, when the Fitchburg Line was built, the Clark family owned a triangular lot bounded by the new train line, Common Street, and Clark Street. Wellington Brook ran along the north side of the triangle, just south of the Fitchburg Line. Royal Road and Dunbarton Street did not exist. After more than a century of Clark descendents the land was sold in 1931 to the Glendower Trust, a vehicle of real estate developers John Hubbard and Donald Kenyon.

Hubbard and Kenyon laid out plans for Dunbarton Street and Glendower Road (shortly after renamed Royal Road). The developers donated the land between Royal Road and the Fitchburg Line to the town after the Selectmen, sitting as the Board of Survey, determined that houses should not be built over the town’s emerging infrastructure along the railroad tracks. The Board of Survey voted that “if the petitioner deeds the land adjoining the railroad to the Town the subdivision will be approved.”

In 1932, Belmont Town Meeting accepted the Royal Road land. The warrant article on which Town Meeting voted designated the Royal Road parcel “for park or playground purposes,” but although the land is listed in Belmont’s inventory of recreational land, the town has never devised a park or recreational use for it.

Instead, in November 1933, the town embarked on a massive federally supported project to bury Wellington Brook from Pequossette Park to Clay Pit Pond and beyond. This project was championed by J. Watson Flett, then chair of the Select Board, who made several trips to Washington, DC, at his own expense to successfully lobby Congress for funding. In 1936 the federal Work Projects Administration established an office in Belmont Town Hall which oversaw the Belmont project and others until 1942.

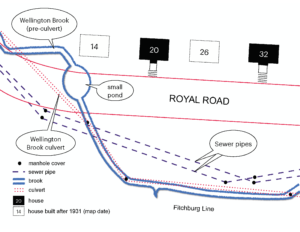

Thus, less than 18 months after being acquired by the town, the Royal Road parcel became the site of a major water infrastructure project. Some features of this project are still visible, including a short segment of the six-foot diameter Wellington Brook culvert. The parcel is also traversed from west to east by two sanitary sewer pipes built at the same time and dotted with 13 manholes.

In subsequent decades, the area became an informal dump. It is filled with construction debris, including large sections of granite curbing, mortared stone wall, and chunks of asphalt. On the north side of the property along the Fitchburg Line, used railroad ties are strewn about along with other railroad-associated trash including metal buckets and hardware used in the ongoing replacement of the Fitchburg Line tracks and ties.

Presumably most trees were cleared for construction of the Wellington Brook culvert and the two sewer lines. Over the ensuing 85 years, invasive species have asserted dominance over native species. The area around the pond is choked with Japanese knotweed, which also extends west over halfway to Clark Street. Other prominent invasives include Asian bittersweet, garlic mustard, burdock, and Norway maples. However, the land also contains older oak and elm trees, a few silver maples, mature sycamores, and attractive native plants such as Solomon’s seal, and is host to pileated woodpeckers and red-tailed hawks, robins, and crows. Mallard ducks frequent the pond.

Features of the Royal Road Woods

The dirt jumps experiment (see “Whither the Royal Road Woods?” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, January 2022) has created an opportunity to think more broadly about the potential uses of the Royal Road Woods. Before discussing specific uses, however, it may be useful to review the central attributes of the parcel and the constraints on its use.

- It contains a pond, a bordering marshy area, and a buried stream, the makings of an ecologically rich and aesthetically pleasing site.

- It is contiguous with the Lone Tree Hill property across Pleasant Street, and deer and wild turkeys can be spotted there.

- It is a two-minute walk to Leonard Street. The area could be enjoyed by patrons of Belmont Center businesses, commuter rail users, and local residents. Pressure for transit-linked housing development may increase the number of residents in Belmont Center in the future.

- Royal Road is heavily traversed by bicyclists and pedestrians, including Belmont High School students. Many people walk on the unpaved northern side of the street. Better pedestrian and bicycle facilities could improve both their safety and user experience.

When the Belmont Community Path is built, it will attract even more pedestrians and bicyclists to the area as the community path will be accessible from Royal Road both via the existing Clark Street Bridge and the pedestrian underpass next to the Lions Club. A park would become a destination for community path users.

The trees lining both sides of Royal Road cool the street and create a welcome woodsy respite from the more urban Concord Avenue and Leonard Street. It was the secluded environment that made construction of the bike jumps possible.

Among the constraints on any use of the Royal Road land:

- The MBTA right of way extends between 29 and 54 feet south of the Fitchburg Line eastbound track; the right of way is wider near the Clark Street Bridge and Belmont Center Station, narrower in the center. The MBTA property is littered with railroad ties and trash. The lack of any barrier between the tracks and the town-owned land creates a potential risk, and dirt jumpers have been observed on the tracks.

- Wetlands fall under the jurisdiction of the Conservation Commission.

- Lower Royal Road, particularly the north side, serves as a spillover parking zone for events at the Lions Club, including the Christmas tree sale, and for Town Day in Belmont Center. That parking capacity needs to be preserved.

Possible uses of the Royal Road Woods

Though the parcel spans only 2.1 acres, it encompasses a variety of microenvironments from the open, wet east to the hilly middle to the flat, sunken west, and from the illuminated edge to the mostly shaded, secluded interior. What follows is not intended to be a comprehensive account of all possible uses of the land. A mixture of uses may achieve the most satisfactory outcome for the largest number of residents.

1. Dirt Jump Bike Park

There is a strong constituency for this use, and in particular for leaving it a kid-directed play area. However, the Select Board’s concerns about liability are justified. The best course for dirt jumps proponents is almost certainly to try to persuade the town to go “all in,” which is how similar bike facilities are being pursued by bike park proponents in Arlington and Waltham.

Such an undertaking might follow this sequence:

- Research by project advocates on similar parks, followed by

- Visioning process for the Belmont land and context, then seeking

- Endorsement of that vision by relevant committees (the Recreation Commission, the Conservation Commission),

- Approval by the Select Board,

- Appropriation of funds for park design by Town Meeting (probably Community Preservation Act funds),

- Park design,

- Approval of construction funding by Town Meeting (again likely CPA funds),

- Finally, construction

While it seems highly unlikely that the kids who built the dirt jumps would be around to enjoy the fruits of that drawn-out process, that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth pursuing for their younger siblings and future generations. The result of such a process would very likely be a fixed course, built to design specifications and not subject to substantive alterations. Ways in which kids could influence development of such a park are discussed below.

2. Daylighting Wellington Brook

The opening of old culverts to resurface streams is called “daylighting” (See “Daylighting Streams Improves Water, Life,” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, May/June 2013). Daylighting requirements include adequate stream slope to ensure flow and space around the stream to rebuild banks, both of which appear to be in place along the Royal Road culvert.

It is well established that natural streams:

- improve water quality via exposure to air, sunlight, vegetation, and soil, all of which help transform, bind up, or otherwise neutralize pollutants, and recycle nitrogen;

- foster complex riparian ecosystems in which insects, birds, aquatic animals, and water-loving trees, among other species, can thrive;

- slow water flow and reduce downstream flooding by providing a surface for water absorption (regenerating groundwater), thereby improving climate resilience;

- are pleasing to the senses and can be the focal point of parks and gardens.

Burying streams negates all those positive effects. In addition, the wetlands at the bottom of Royal Road, when flooded after heavy rain, currently drain into the street and flow into a sewer grate where the water feeds into the storm drain system, rather than the brook as it should. Daylighting would re-channel that water into Wellington Brook, reducing combined sewer overflow and ultimately the burden on sewer water pumping, treatment plants, and ratepayers.

Drawing adapted from a 1931 Town Engineer’s map showing course of Wellington Brook before and after construction of the buried culvert. Source: Vincent Stanton, Jr.

Technical support for daylighting projects is provided by the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration, which also has a small grant program that funds engineering and design for culvert replacement, dam removal, and daylighting projects. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and the US Environmental Protection Agency have also funded daylighting projects in the past. There are ongoing daylighting efforts across the Commonwealth, including projects in Boston, Lexington, Lincoln, Braintree, and Weymouth.

Important questions regarding the potential daylighting of Wellington Brook include:

- Some of it or all 1,000 feet of it?

- What course should the brook follow at the bottom of Royal Road?

- What is the condition of the 1930s culvert? Should daylighting be accompanied by partial culvert replacement?

- What degree of “naturalization” (landscaping, flood plain) of the surroundings should accompany the daylighting project?

From an ecological and aesthetic perspective, ideally all 700 feet of the culvert that passes through the Royal Road woods would be opened. However, from a cost perspective, and considering the broad support for a bike park—which would have to conform to wetlands laws—it may be more practical to consider opening the eastern 200 feet (approximately from 14 Royal Road to 26 Royal Road) as a first phase. About one quarter of that distance (50 feet) would traverse the existing wetlands, which are mostly located east of where the culvert turns under Royal Road at #14.

In one alternative, the daylighted brook would cross under Royal Road via the existing culvert across from 14 Royal Road. A more ambitious alternative would be to eliminate a segment of the westbound lane of Royal Road at the far east end of the woods, moving it south to join the eastbound lane on the south side of the War Memorial island (while keeping a stub road in front of the Lions Club to allow parking for commuter rail users). That would join the green space in front of the Lions Club to the Royal Road Woods, and permit Wellington Brook to traverse its original course, crossing in front of the Lions Club south of the war Memorial island before entering a short (about 45 foot) existing culvert beneath Common Street. (The war memorial was erected a decade before Wellington Brook was buried.)

Reinforced concrete pipe can last well over 100 years depending on the quality of construction and the environment it is exposed to. However, if inspection of the 1930s Belmont culvert shows it is nearing the end of its service life, the daylighting project could be combined with a culvert replacement beneath Common Street. In the event of culvert replacement, extending the daylighting project all the way to Common Street could be accomplished at a lower cost to Belmont taxpayers due to a higher likelihood of external funding.

Daylighting should be accompanied by an ambitious landscaping plan to realize the full aesthetic and ecological potential of a healthy Wellington Brook. It would be a transformative project, visible daily to hundreds of people.

3. Reforestation

In September 2021 a dense, diverse planned forest comprising about 50 native species was planted by a group of volunteers in a small patch of land (4,000 square feet), in Danehy Park, Cambridge, using methods developed by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki.The Miyawaki approach, widely implemented in Japan and several other Asian countries, starts with clearing all existing plants, often including invasive species, and is designed for rapid growth of forests up to 30 times denser than usual. The forests are expected to be maintenance-free after three years.

The mix of species, customized to the Cambridge site, included chokecherry, elderberry, maple, dogwood, sumac, aster, hazelnut, witch hazel, rose, and others. Species that attract pollinators and that produce food for birds and other animals are essential. Perhaps, in a nod to Belmont’s agricultural past, fruit-bearing plants could be incorporated into the mix.

The survival and growth of each plant at the Danehy site will be tracked by volunteers. Such dense vegetation can enhance carbon capture, potentially providing a modest boost to Belmont’s climate goals, and can be visually striking.

Whether the Miyawaki approach is right for the Royal Road land is not clear. On a large scale it is not really compatible with walking paths. However, areas as small as 30 square feet have been planted. Regardless of the methods, the existing invasive species would need to be cleared to create space for a more diverse mix of native species.

4. Mixed Uses

The optimal use of the Royal Road land, at least for the present, may encompass a soft division of the Royal Road Woods, with a dirt bike park located west of 32 Royal Road (where the most widely used entrance to the dirt jumps is located), and a pocket park focused around Wellington Brook to the east, with native trees and a walking path. That division would give the bike jumps the widest and best-shielded territory where the vast majority of the jumps have been built, while preserving for more contemplative visitors the smaller, but potentially more scenic area to the east, only steps from Belmont Center.

The use of the western half for a bike park should not prevent planting more native species—indeed, to the extent that the woodsy, secluded feel enhances the experience at the bike jumps, better landscaping should be viewed as an asset. The plan for the bike park should also include adequate earth for jump construction to halt the practice of excavating deep pits that undermine existing trees and create the potential for falls.

Inclusive Planning and Implementation

As noted above, one crucial element of the dirt jumps has been the kid-directed nature of its creation and operation. That won’t be possible in the same way with a planned park. For safety reasons, and to prevent the obliteration of all plants, there would be constraints on the scale and location of the jumps.

However there should be greater scope for kids to participate in the development and implementation of a comprehensive plan for the woods that includes not only the track layout and jumps but also landscape design, planting and maintaining trees, shrubs, flowers, and grasses that enhance the bike park. The landscaping aspect may not appeal to all the kids that built the jumps, but it may draw in new participants with different interests. In short, the design and construction of the park should be managed to maximize youth participation. An article in the November 2021 Newsletter (“Urban Trees Improve Everyones’ Lives”) cited two local programs that engage teens in forestry projects.

The Select Board promised on May 5, 2021, to revisit the possibility of continuing the dirt jumps at the Royal Road Woods. As with all public land, an inclusive and deliberate planning process will be necessary to move any plan forward. The intent of this article is to expand the discussion of what is possible. See the online version at www.belmontcitizensforum.org for additional information and context.

Vincent Stanton, Jr. is a director of the Belmont Citizens Forum. He has lived on Royal Road since 1992.

BONUS MATERIAL

Belmont’s Biggest Infrastructure Project

The Belmont Citizen of November 3, 1939, (page 1) briefly recounts the history of the Wellington Brook culvert project:

“By Thanksgiving finishing touches are expected to be put on the final link in Belmont’s six-year project to put Wellington Brook underground….

From its source at the Pequossette Playground on Trapelo Road to the Clay Pit Pond, Wellington Brook is already underground in huge round concrete culverts, except where it flows through the Underwood estate, where the owners of the property preferred the open brook for its scenic effects.

Work on one section or another of the culvert, the total length of which is over 8,160 feet, has been going on, and providing jobs, since June 1933, when the Belmont Unemployment Emergency Committee put thirty men to work between the pond and Cottage Street as a community project before federal relief agencies were started.

In November of that same year Chairman J. Watson Flett of the Board of Selectmen obtained the first federal grant toward the construction of a long culvert from Royal Rd to Trapelo Rd and Belmont became the first town in Massachusetts to actually get CWA relief work under way. Eight men were employed on the project at the start and for the next five years varying numbers of relief workers were kept busy on the $300,000 project, over 80% of the cost of which was furnished by the CWA, ERA and WPA. Besides providing an efficient storm water outlet for a large part of Belmont, the culvert project has done away with a mosquito nuisance and improved the appearance of the town.”

Notes:

The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a short-lived job creation program established in the early days of the Roosevelt administration, under the authority of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA, or just ERA). The CWA ended on March 31, 1934, after spending $200 million a month and providing jobs to four million people. The Belmont project was subsequently funded by the Works Projects Administration, enacted in May 1935 as part of the “second New Deal.”

The headwaters of Wellington Brook were originally near the Bradford building in Cushing Corner, per an 1875 map of Belmont (Middlesex County 1875, F.W. Beers), and from there flowed northwest through what is now Pequossette Playground before turning north to cross Waverley Street, and then northeast near the Fitchburg Line. As an aside, note that the owners of the Underwood estate, who included architects and landscape designers, “preferred the open brook for its scenic effects” while the article concludes (presumably reflecting the consensus view) that the project “improved the appearance of the town.”

Inventory of Trees in Royal Road Woods

The author, by no means a naturalist, attempted a complete inventory of trees in the 2.1 acre Royal Road Woods. Setting the threshold at a 3-inch minimum diameter trunk and at least 15 feet tall, there are approximately 393 trees. Norway maples are by far the dominant species, comprising over 80% of the total. They are particularly prominent around the edges of the property. Other species identified include 27 elm (and at least a dozen dead or dying elms), 11 oak, 4 sycamore, 4 linden, 3 silver maple, 3 northern catalpa, 3 pine, and about a dozen unspeciated.

Value of Unsupervised Play in Natural Settings

Construction of the bike park was conceived and executed by children. That has become rare in the 21st century (the author, age 66, and the father of two, speaks from experience) and deserves celebration. Sara Stein’s book on the topic of children’s play, Noah’s Garden, was reviewed by Carol Stocker in the Boston Globe (March 1, 2001). Stocker summarized the thesis:

“An ecological call to arms, she [Sara Stein] thinks adults have sabotaged child development by replacing woods and farmlands with unusable, unengaging, suburban landscapes. ‘I think it’s a necessity of children to have a natural environment to become fully human. Children these days are suffering from being separated from exploratory and sensory experience. What they have is not an environment, it’s a lawn, there’s nothing there for children to explore. Instead, we have plastic. No child knows that apple jelly comes from apple trees. There’s a divorcement.’

She believes independence to explore away from parental monitoring is important for children. She would like to see wild areas restored to the verges and backs of adjoining suburban properties to create ‘rivers of naturalness’ that would become unmanicured lay areas for forts and tree houses.”

What Goes into a Public Playground?

According to the Massachusetts Playground Safety Fact Sheet (see links at end of article):

“Playgrounds are the setting for most of the injuries sustained by children aged 5 to 14 in the school environment. A special study of playground injuries and deaths conducted in 2001 for the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission found that each year emergency departments treat more than 200,000 children, ages 14 and younger, for playground-related injuries. Approximately 45% of those injuries are severe.”

A presentation on limiting municipal playground liability at the Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) notes that Massachusetts law limits municipal liability for injuries at playgrounds and parks to situations where the government entity (e.g., Belmont) is negligent in maintaining safe conditions, and points out that supervision is crucial to limiting liability:

“Although the design and condition of equipment are important, the most critical safety element is supervision. When a public entity is responsible for supervising children, liability becomes a significant consideration. The responsibility of recreation department and school employees to supervise activities is where the true liability exists. Playground supervisors should be trained before being given this enormous responsibility.”

Unfortunately, if the jumps are designed and built by kids, the town has no control over whether the conditions are safe, a seemingly impossible arrangement for the town.

There are a variety of exculpatory agreements the town could theoretically employ, from requiring parents to sign liability waivers for their children to posting “Enter at your own risk” signs, but such measures are unlikely to be unattractive to parents and probably unlikely to assuage the town’s liability concerns, particularly given a user population that includes 9 and 10 year olds.

Another consideration is that any publicly funded bike jumps would likely have to be accessible to all, per the Americans with Disabilities Act and corresponding Massachusetts law.

Bike Parks in Surrounding Towns

A new nonprofit organization called the New England Cycling Center has proposed a Waltham bike park to include an outdoor velodrome, a BMX track, a pump track, a bicycle playground, two to three miles of dedicated dirt bike trails and 3.1 miles of paved bicycling and running trails on four acres, as well as (in a separate, more costly proposal) an indoor velodrome and fitness center. The proposal was reviewed by the Waltham City Council on June 14, 2021, and referred to the Fernald Reuse Committee for consideration.

Arlington is further along with a less ambitious plan: aMountain Biking Working Group studied four possible sites for a park with moguls and ramps, somewhat like the Belmont jumps, and recently settled on Hill’s Hill, a woodsy area near Summer Street. The town has hired a design consultant to conduct a feasibility study of that site. A public meeting held September 23, 2021, included a slide show update (see links). If the project moves ahead per plan, funding for construction will be sought in fiscal year 2024.

Daylighting Projects Nearby

Two recent daylighting projects in Lexington: a 280-foot segment of stone culvert draining Willard’s Pond was recently opened by the town, and the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration (DER) is partially funding the daylighting of a 175-foot section of Kiln Brook. Currently buried in a 36-inch diameter culvert, the brook will run in an open channel constructed of geotextiles, gravel, and stone, with a vegetated retaining wall around a box culvert.

In Lincoln the stream at Sunnyside Lane was daylighted in a project that involved support from the Massachusetts DER in partnership with the National Parks Service.

Weymouth and Braintree cooperated in a project that included daylighting a section of Smelt Brook and creating a small public park around the stream. The project (which included other elements) was funded by two MassWorks Infrastructure Grants worth a combined $2.2 million.

Miyawaki forests

The Miyawaki forest concept, based on dense planting of complementary native species, requires local adaptation. The Danehy Park forest planted last fall is apparently the first in the Northeast. It was designed by Ethan Bryson of Natural Urban Forests, a Seattle non-profit affiliated with Afforestt, a larger Indian organization that designs and installs tiny forests. Bryson selected the species after study of the northeast flora and the site.

A non-profit in The Netherlands called IVN Environmental Education, has planted 200 Miyawaki forests in that country in the last six years. Researchers at Wageningen University in The Netherlands have observed 595 different species of animals and plants in the Tiny Forests, and have measured about 125 kilograms of carbon dioxide captured per 100 square meters (~1,000 square feet) of forest per year.

Annotated Links

Massachusetts Park closure after COVID-19 outbreak

Baker-Polito Administration Announces Temporary Closure of State Park Playgrounds and Other Facilities (Parks Remain Open for the Public to Visit). Released March 18, 2020:

https://www.mass.gov/news/baker-polito-administration-announces-temporary-closure-of-state-park-playgrounds-and-other-facilities

Belmont dirt jumps links

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/240314584507062/

Instagram: @belmontdirtjumps

change.org petition with 984 signatures:

https://www.change.org/p/belmont-board-of-selectman-to-legalize-building-and-riding-at-the-belmont-dirt-jumps

Belmont Select Board discussion

May 5, 2021 Select Board meeting – discussion of Belmont dirt jumps at 32:24 – 37:30:

https://belmontmedia.org/watch/belmont-select-board

Bike park proposals in Arlington and Waltham

Arlington selects Hill’s Hill for a mountain bike park; feasibility study slide presentation:

https://www.arlingtonma.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/58484/637707560346930000

The New England Cycling Center has proposed an extensive Waltham bike park:

Playground safety and liability

Massachusetts Playground Safety Fact Sheet:

https://www.mass.gov/service-details/playground-safety-fact-sheet

Massachusetts Municipal Association blog post “Safe playgrounds can help to reduce municipal liability”

https://www.mma.org/safe-playgrounds-can-help-to-reduce-municipal-liability/

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) Public Playground Safety Handbook lists voluntary safety guidelines and suggested maintenance checklists as well as equipment testing procedures for playground safety audits:

www.cpsc.gov/cpscpub/pubs/325.pdf

National Park and Recreation Association: Certified Playground Safety Inspector (CPSI) training and certification program:

https://www.nrpa.org/certification/CPSI/become-a-cpsi/

Daylighting streams; ecological value of healthy streams

Daylighting explained and the culverting of Belmont streams reviewed in the BCF newsletter:

https://www.belmontcitizensforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/BCF13MayJuneWEB.pdf

Comprehensive report on daylighting (circa 2000) prepared by the Rocky Mountain Institute for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Includes discussion of technical aspects and examples from across the United States:

Advantages of daylighting buried streams (content excerpted from the Rocky Mountain Institute report cited above, in a short one page format):

https://megamanual.geosyntec.com/npsmanual/streamdaylighting.aspx

Ecological value of healthy streams, from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service:

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/technical/?cid=nrcs143_014199

For details of the Weymouth/Braintree daylighting project see this article by the Sierra Club:

Miyawaki reforestation

Miyawaki forest created at Danehy Park, Cambridge by over 100 volunteers, September 2021:

https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2021/10/20/miyawaki-forest-danehy-park-cambridge/

Step by step instruction on how to create a dense mini-forest (species vary by location):

https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/how-to-make-mini-forest-miyawaki-method-34867

Small fragmented urban forests are highly efficient at carbon capture

Research article: Sarah M. Garvey et al. (2022) “Diverging patterns at the forest edge: Soil respiration dynamics of fragmented forests in urban and rural areas” Global Change Biology https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.16099

WBUR article “Urban forests may store more carbon than we thought, study finds”: https://www.wbur.org/news/2022/02/16/forest-fragments-northeast-us-climate-change-soil-respiration

The Netherlands Miyawaki forest program (over 200 forests in the last five years):

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/why-tiny-forests-are-popping-up-in-big-cities

Maps

Figure 8 in this story is Plate 016 from “Atlas of Watertown, Belmont, Arlington & Lexington” Published by Geo. W. Stadly & Co., 1898.

http://www.historicmapworks.com/Map/US/1568524/Plate+016++

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.