By Julie Wormser

Once upon a time, images of climate change featured skinny polar bears on melting ice floes, and hot, dusty desertscapes. Tragic for sure, but also very far away in time and space.

Not any more.

Last summer’s alarming weather—from 120 temperatures in the Pacific Northwest to record flooding rains here in the Northeast—has brought the immediate effects of climate change into sharper focus and more local concern.

In Greater Boston, the most likely risks we need to prepare for are:

- flooding from intense rainfall and coastal storms/sea level rise,

- hotter, drier summers,

- less predictable winter weather, and

- bigger storms with higher winds.

We are learning more all the time about the cascading challenges that come with these changes, such as crop failures, overtaxed stormwater systems, and increases in heat-related illnesses such as asthma and heart attacks.

Luckily, both Belmont and the Commonwealth are being proactive in helping to prepare people and places for the worsening weather associated with a warming planet. In 2020, Belmont completed its joint hazard mitigation/climate vulnerability plan (bit.ly/BCF-MVP) that identifies the most pressing needs over the coming decades. (See “How to Help Belmont Survive Climate Change,” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, March/April 2021.) Led by Glenn Clancy, town engineer, both the process and the plan were among the region’s best. Next time you see one of Belmont’s hard-working town employees, please thank him or her for their great work.

Belmont’s plan was accomplished with a grant from the state Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness program and unlocked additional funding for the town to take actions to prepare for worsening weather. (See “Belmont Awarded Climate Change Grant,” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, January/February 2022.) Last year, Belmont received nearly $200,000 to develop a sophisticated computer model to understand current and future stormwater flood risks and was needed in order to create an effective infrastructure improvement plan.

Belmont is not the only community experiencing more intense rainstorms, and most actions needed to alleviate the impacts cross municipal boundaries. At the same time, Massachusetts lacks the formal regional government structures needed to plan, finance, and implement regional climate resilience measures.

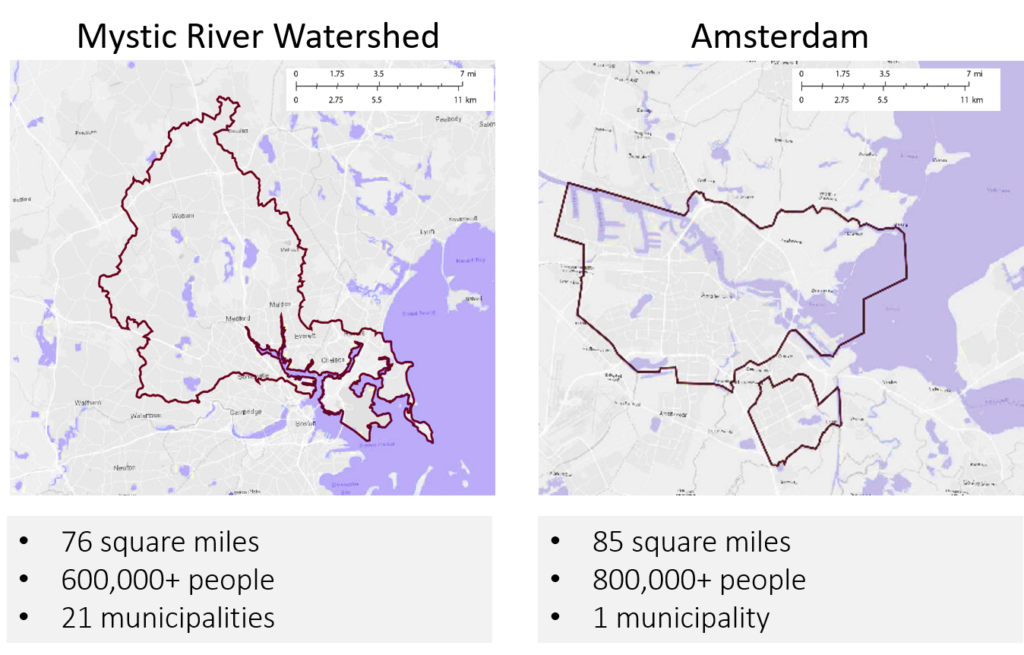

The Mystic River watershed is approximately the size of Amsterdam, or the borough of Brooklyn, New York. Instead of being a single city (or part of a city), the Mystic watershed comprises at least part of 21 cities and towns, each with its own government, budget, culture, and regulations. A sense of urgency and commitment around climate resilience drove senior municipal staff from 10 communities to form the Resilient Mystic Collaborative (RMC), in order to pursue hands-on regional projects that no community could tackle alone.

One driving goal is closing the gap in climate resilience between those people and businesses able to manage extreme weather without harm, and those who can’t. As with the pandemic, vulnerable residents are often historically underrepresented minorities experiencing economic hardship, who may also have challenges such as language barriers, outdoor jobs, and/or fragile health.

In its first three years, the RMC grew to include 20 communities—including Belmont—covering 98% of the Mystic watershed. RMC communities have raised more than $10 million for climate resilience; half for regional projects, and half for local projects. Staff from the Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) and CH Consulting are funded by the Barr Foundation to provide additional capacity for municipalities to work regionally. Here are some of our early successes.

Wetlands Identification

Together, Belmont and other communities in the Upper Mystic watershed identified and ranked over 460 possible stormwater wetlands to help manage local and regional flooding while increasing both habitat and outdoor recreational opportunities. The first five restoration projects are pursuing design and permitting funding this year. These projects take as inspiration Cambridge’s Alewife Stormwater Wetland, a three-acre constructed wetland that provides tremendous recreational and habitat values while improving stormwater quality.

Storm Planning

The Lower Mystic watershed, stretching from Assembly Row in Somerville through Winthrop and Revere, is home to both the highest concentration of critical regional infrastructure between New York and the North Pole, and to the highest population of environmental justice residents in New England. After a two-year vulnerability assessment to understand how infrastructure and vulnerable residents would be harmed by a major coastal storm, communities are seeking over $100 million from the federal Infrastructure Act to protect New England’s produce distribution center and inland businesses and residences from saltwater flooding. One of these projects is the Island End River in Chelsea and Everett, which is experiencing increasing coastal flooding.

Summer Risks

We’re working together to get ready for hotter summers. Greater Boston is a blizzard culture. Our houses have steep roofs to shed snow, and our regulations require landlords to keep heat on in the winter. We know to shelter in place during winter storms, and to remember to help shovel out elderly neighbors afterward.

Not being used to dangerously hot summers, however, our architecture, regulations, and culture are not prepared for multiple days over 90ºF. Pavement makes things worse. Temperatures in big, treeless parking lots can top 100ºF while a nearby wooded area is a safer 85ºF. Last summer, more than 80 volunteers measured relative heat, humidity, and air quality during an August heatwave in a joint project of the RMC and the Boston Museum of Science called Wicked Hot Mystic. These heat maps will be used to identify dangerously hot neighborhoods and to work with interested residents and businesses to come up with solutions to keep people safe.

Wicked Hot Mystic monitors Melanie Carte (left) and Sarah Benson (right). Source: Mystic River Watershed Association

We’ve all been through a rough several years. Many of our challenges predate COVID. Working together for our common good is not only hopeful, it can be joyful. Never forget that we’re in this together.

Julie Wormser is senior policy advisor for the Mystic River Watershed Association

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.