By Jane Sherwin

For about a century, areas around Boston that are now suburban housing were in many cases devoted to market gardening. Arlington, Lexington, Belmont, Watertown, Brighton—all grew produce very profitably.

A market garden, sometimes known as a truck farm, produces on a small scale a variety of fruits and vegetables for local markets. Around Boston, this intensive form of farming was supported by heated greenhouses. The market gardens were so close to Boston that they had no need to pay railroad charges, using their own trucks and wagons instead. The gardens were profitable, and families could afford the education needed for the engineering and science of market gardening, including the complexities of greenhouse management. They could also afford the growing real estate taxes: suburban land was, as one market gardener said, “taxed highly and costs us very dear.”

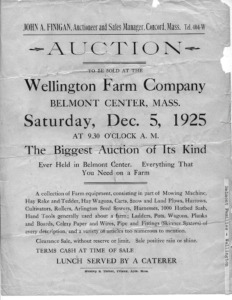

In Belmont, the Wellington Farm Company held 36 acres of greenhouses and open farm land. Imagine standing in front of the Town Hall annex looking east toward what is now the Winn Brook School. One hundred years ago, you would have seen fields full of greenery, the sun sparkling and reflecting off the Wellington Market Gardeners’ greenhouses. They grew celery and onions outdoors, and the air was full of the smell of celery. They also grew carrots and beets, squash, tomatoes, and had two acres of Williams apple trees. There were three acres of heated cold frames for lettuce and dandelion greens, and they grew lettuce, watercress, and mint in the greenhouses in the winter, and cucumbers in summer. But in 1925, the entire Wellington Farm apparatus, from mowing machines to celery paper, was auctioned off.

Market Gardening Technology

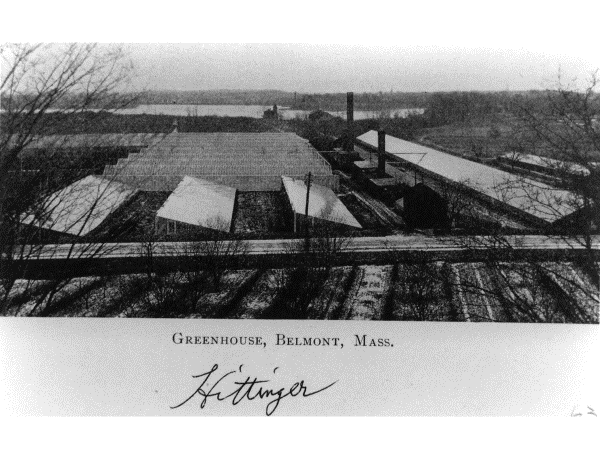

Greenhouses made market gardening profitable as a year-round enterprise, although 100 years ago this meant using coal for heating. Brick smokestacks dotted Belmont’s skyline. Oxalic acid from coal smoke is corrosive and can cause severe irritation and burns to skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. When the Boston Chamber of Commerce visited the Hittinger Fruit Company in 1915, they reported that “from 850 to 900 tons of coal are burned during the year to keep these glass houses at the necessary even temperature.”

Belmont’s Farming Families

Many of Belmont’s market gardens began with colonial settlers whose descendants adapted to the changing economy. Consider the Frost Farms, located on the east side of Belmont along Pleasant Street and down Brighton Street. There was Jonathan Frost, who entered the market garden business and built the beautiful yellow house on Brighton Street, and the 1827 Thaddeus Frost house a little to the north. After Jonathan Frost’s death in 1873, his son Artemus became a “well-known specialty grower of fruits for the Boston Market.” These gardeners were Sylvester Charles Frost, born in 1842, a market gardener; Frank C. Frost, born in 1854, in the “business of farming”; and Harold Locke Frost, president of the Massachusetts Fruit Growers Association, president of the Frost Insecticide Company, and a trustee of the Massachusetts Agriculture College.

The Hittinger Fruit Company

The Hittingers were another leading Belmont market gardening family. In the mid-19th century, the firm of Gage, Hittinger & Co. was a major ice harvester and shipper with markets worldwide. Fresh Pond was one of their major sources of ice. In 1847, Jacob Hittinger purchased 40 acres of land on the west side of Fresh Pond and turned to “experimental agriculture.” For more than a century, until 1956 when the land was sold for housing, the Hittinger family gained a wide reputation for excellence in farming and market gardening.

The Hittinger Fruit Company offered an extraordinary range of produce. In 1915, the Boston Chamber of Commerce undertook “Industrial Excursion No. 10,” a visit to the “Belmont Farm of the Hittinger Fruit Co.” You notice the language, of course: the farm is considered an industry, a part of the commercial life in which the Chamber of Commerce had a real interest. The excursion reports:

“More than three acres are under greenhouses, and the rest of the farm is largely devoted to the culture of fruits. In the outside may be seen “three-story farming,” the first-story crop being radishes, parsley, and strawberries growing next to the two-story bushes of currants and gooseberries, these being in turn next to the upper-story crop of cherries, apples, pears and peaches.”

The 40 acres which Jacob Hittinger purchased include parcels that abut School Street and Fresh Pond today. In your mind’s eye, start at the intersection of Belmont and School Streets, and take yourself down School Street, past Fairview and Elm and Bacon, to number 450. A small granite post marks what was once the entrance to the Hittinger company produce store.

Picture 20 soccer fields stretching away along School Street and extending all the way down to Fresh Pond. There were cherry trees, quince bushes, apple trees, peach trees, currant bushes, and if it were spring, they would all be in bloom.

Jacob Hittinger’s grandson, also Richard, continued farming the land right into the 1950s. In 1976, Town Meeting passed a resolution honoring him for his contributions “to the Belmont community during its years of transition from a farming town to an attractive suburban community.” Richard died in 1982.

Immigrant labor was essential for harvesting. On the Hittinger farm, according to a Chamber of Commerce report, “from 25 to 75 helpers are employed in taking care of the farm, the larger number being employed during the fruit season when pickers are needed.” Some seasonal laborers in Belmont probably came up from the North End, and some lived in Waverley Square or in the neighborhoods east of Clay Pit Pond.

Belmont’s 20th-century Farms

Clearly we can think of Belmont before 1950 as a community in which farming and housing development were of similar weight and significance. In 1916, when Joe Errico was beginning to harvest onions at the Shaw Estate, William Poole was selling to developers the 21 acres, no doubt orchards, he had bought in 1904 and 1910 on the corner of Common and Washington. In 1925, when the Wellington Market Gardeners land was sold for housing, Walter Lenk was just beginning his Belmont Gardens company and the patenting of his famous Belmont gardenia.

Ralph Stevens’s memory of scything hay in town is a picture of this overlapping of old and new. He recalls Farmer Thomas and his team cutting the long grasses that must have grown along the streets around town every year. “I can distinctly remember—oh this is marvelous—to see them stop every half hour [and] take out a whetstone and I can still hear the noise as they whetted and sharpened their scythes, the long bladed scythes for cutting hay.”

Jane Sherwin is a Belmont resident with an interest in Belmont’s agricultural history.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.