By Greg Harris

Since developers have targeted the Alewife area for rapid development, with housing interests erecting massive apartment complexes and life sciences companies rushing to turn the area into a second Kendall Square, long-time residents have feared the trampling of their history, quality of life, community health, and the remaining natural environment. But these changes present opportunities as well as risks.

If a coalition of long-time residents and neighborhood activists get their way, life science developer IQHQ’s $125 million dollar acquisition of land next to the Alewife T Station may result in the resurrection of Jerry’s Pond. This neighborhood landmark has been fenced off due to pollution for nearly 60 years, but it offers a chance for a restored and accessible natural reservation.

Environmental sustainability—and justice

To understand the appeal of a long-inaccessible pit sitting on industrial land and what moved Cambridge’s City Council to unanimously pass a resolution pushing for it to be restored to public use, consider both the neighborhood’s present needs and its enduring history.

The present needs are not hard to define. Drowning in traffic, with a skyline set to be crowded by ever-more condominium complexes, office buildings, and laboratories, the Alewife region must act now to preserve and enhance its green spaces, parks, and open corridors or see access forever lost.

An aerial view of Jerry’s Pond. Russell Field is in the left foreground: Route 2 and Alewife station are visible at the top of the photo. Source: Friends of Jerry’s Pond

Floodwater management is a large concern. Alewife sits at the heart of what used to be called the Great Swamp, stretching from Little Pond in Belmont and Spy Pond in Arlington down to Fresh Pond in Cambridge and draining to the Mystic River via Alewife Brook. When storm surges and sea level rise threaten, the remaining natural water features of the landscape need to be preserved and expanded. Though Jerry’s Pond was created by digging clay, it is part of the Great Swamp. The land fenced in along the pond’s edge is among the largest stretches of undeveloped green space in Cambridge that has not been set aside for conservation. It also has a rare gem, a thriving six-acre pond with an annual great blue heron rookery.

Jerry’s Pond represents an issue of environmental justice. Alewife holds Cambridge’s greatest concentration of affordable housing, including the Jefferson Park apartments just across the street and the Rindge Towers, three Le Corbusier-style high-rises with 777 housing units. The 4,000 people living in these units—disproportionately poor, and composed significantly of people of color and recent immigrants—have for decades faced a polluted, fenced-off property. As neighborhood activist Eric Grunebaum, a cofounder of Friends of Jerry’s Pond, puts it, “It’s no coincidence that the City of Cambridge has mostly taken a hands-off approach to Jerry’s Pond’s given where it’s located. If it were located in West Cambridge, there’s little doubt that these issues would have been addressed long ago.”

It turns out that there is political support for Alewife’s green space as well. Cambridge Mayor Sumbul Siddiqui grew up in part in the Rindge Towers and sponsored Cambridge City Council’s resolution on Jerry’s Pond.

“The Cape Cod of North Cambridge”

What could Jerry’s Pond mean to the neighborhood? A glance at its history shows just how much. It was originally excavated from the marshlands of the Great Swamp in the 1860s for its clay, spearheaded by Jeremiah (“Jerry”) McCrehan, an Irish immigrant brickworker who prospered enough to form his own brickmaking company. The “pit,” as it was called, filled back up with water, and by the turn of the 20th century had become a neighborhood swimming hole. From at least the late 1880s to 1961, it was the beach where the working-class residents of North Cambridge spent their summer days off, earning it the nickname “The Cape Cod of North Cambridge.” Not only that: in the 1920s, the J. B. Johnson Company used Jerry’s Pond as a source of ice to manufacture its locally famous ice cream, carving out 10,000 tons of ice blocks a year and storing them in an icehouse next to the pond.

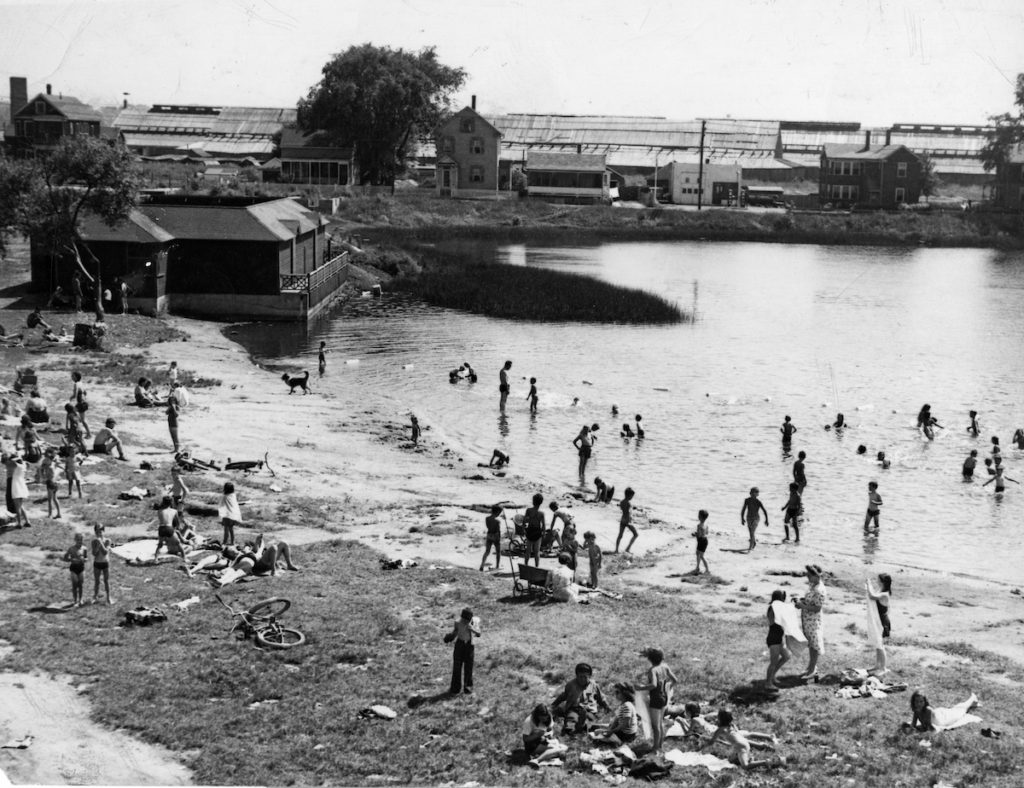

The roots of the nearby land’s eventual pollution problem and abandonment are obvious, though, in early photographs. As sunbathers lay out on the beach and dogs and swimmers frolic in the waters, industrial works loom on the north side of the pond, from brickworks to lumberyards to, most ominously, the manufacturing plants of Dewey & Almy Chemical Company dating from 1919. Waste products were often left in settling lagoons on the site.

In 1954, the W. R. Grace Company purchased Dewey & Almy Chemical. W. R. Grace’s role in polluting Woburn’s waterways was made famous by the book and movie, A Civil Action. In 1961, Jerry’s Pond was fenced off, and the McCrehan swimming pool, named after “Jerry” McCrehan’s grandson, was built on the adjacent Russell Field.

Contaminants still found on the larger site include byproducts of manufacturing rubber—especially DAXAD (naphthalene sulphonate)—and, north of the pond, a large quantity of asbestos once used in brake linings and insulation. The city of Cambridge passed a Council Order in 1914 calling for the purchase of “Jerry’s Pit so called, for the purpose of using it in connection with Russell Field for bathing purposes,” and the city operated a bathhouse there for public enjoyment for decades.

However, the land remained private, limiting Cambridge’s options for cleanup. This proved an obstacle as recently as 2018 when then-Councilor Siddiqui and other residents reached out to the EPA to inquire about a Targeted Brownfields Assessment grant, a crucial first step in determining the current levels of pollution. The Cambridge’s city manager signaled he did not believe Cambridge had standing to pursue the assessment without permission of GCP Technologies (a W.R. Grace spinoff). GCP Technologies refused such permission, writing in a letter that it was instead engaged in a process “to evaluate business options.”

A last best chance?

Those “business options” came to fruition this summer with GCP Technologies’ sale of its headquarters to IQHQ for an astronomical $125 million. Plans have been announced to develop the site as a life sciences campus. The 26.5 acres stretch between Whittemore Avenue and Rindge Avenue and include GCP Technologies’ buildings and parking lots, the fenced-off nine acres of Jerry’s Pond and its perimeter, and the equally fenced-off green spaces on either side of the pedestrian and bicycle path that connects Russell Field to Alewife Station.

Many unknowns surround the sale, including just how much of the purchased land IQHQ intends to develop. Due diligence would have shown IQHQ that much of the undeveloped land is deemed a Massachusetts Hazardous Material Site, subject to an Activity and Use Limitation as well as a City of Cambridge asbestos ordinance.

Those same designations guide the restoration of public access to Jerry’s Pond, particularly the perimeter furthest from the factories, where contamination is thought to be far less extensive. The Friends of Jerry’s Pond envision strolling paths and boardwalks for wildlife viewing, not the return of a swimming beach. And that plan would have to be carefully managed to allay the concerns of long-term neighborhood advocacy associations such as the Alewife Study Group.

Cambridge has weighed in on the side of realism and hope. The city recognizes that other contaminated areas have been safely made into public reservations, such as Belle Isle Marsh in East Boston. At a July 27 meeting, soon after IQHQ’s purchase was announced, the City Council resolved that City Manager Louis D. Pasquale be “hereby . . . requested to contact IQHQ and engage the relevant city departments regarding next steps for restoration, health and environmental protection, improvement, beautification, and making the surrounding areas of Jerry’s Pond publicly accessible.” The goal is “incorporating Jerry’s Pond into the adjacent public parklands, with pedestrian and bicycle connections to the MBTA Station, the Alewife Reservation, Minuteman Bikeway, and the Linear Park.”

Perhaps most encouraging for open space advocates, Cambridge’s “Envision Cambridge” planning process for Alewife, completed a year ago and published as the Alewife District Plan, recommends on pages 111 to 112 that Jerry’s Pond and the large swath of land extending north of the site be restored as green open space.

Pasquale has contacted IQHQ. Now the neighborhood—and the broader region of Belmont, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville, and Medford, connected by human paths and by the remaining waterways of the Great Swamp—waits to see: Will Jerry’s Pond sparkle at the center once again?

Greg Harris is on the Alewife Subsidiary Board of Green Cambridge and resides in North Cambridge. A long-time teacher of writing at Harvard University, Greg is founding editor of Pangyrus Literary Magazine.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.