By Roger Wrubel

Massachusetts adopted An Act Creating A Next-Generation Roadmap for Massachusetts Climate Policy (Roadmap) in 2021. The act directed the Department of Energy Resources (DOER) to update the existing energy building codes and to create a new Opt-In Specialized Energy Code to encourage the construction of all-electric buildings.

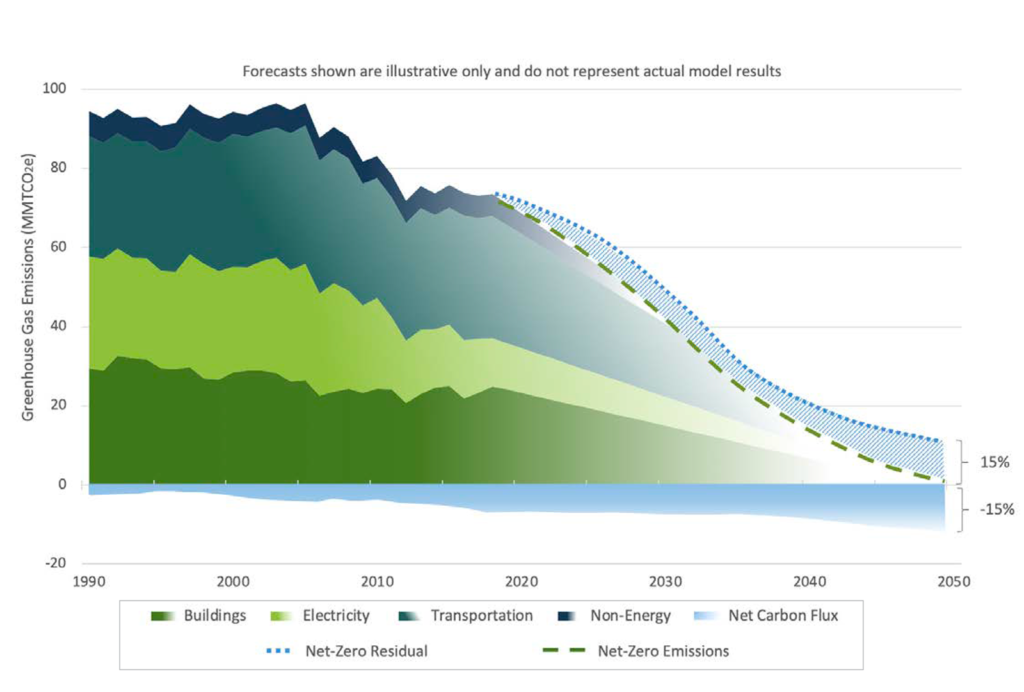

The state needs to update energy building codes because the policy requires reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The policy set greenhouse gas emissions limits of at least 50% below the 1990 baseline by 2030, at least 75% below the baseline by 2040, and required net-zero emissions by 2050. By 2050, emissions will be limited to 85% below the baseline. To meet those limits, we need to reduce emissions from buildings, which means changing building codes.

Municipalities can adopt the Specialized Code by a vote of their town meeting or city council. To date, 18 Massachusetts cities and towns representing 18% of the state’s population have recognized its benefits and have adopted the Specialized Code since it was made available in December 2022.

Greenhouse gas emissions required for different sectors to meet net zero emissions by 2050. Graphic from the Massachusetts 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap.

Policy requires nearly 100% electric power

To achieve the emission reduction goals set by the Roadmap, the Massachusetts energy economy must transition to close to 100% electric power. Electricity is the only energy source available that can be produced without emitting carbon into the atmosphere and destabilizing the Earth’s climate.

With the Specialized Code, the DOER put its thumb on the building-code scale to promote the electrification of all new construction. The rationale for all-electric new construction is that buildings reliant on fossil fuel combustion equipment for heating, hot water, cooking, or clothes drying have no clear path to zero-carbon emissions.

Buildings with electric appliances can potentially become zero-carbon homes. There has been a steady increase in clean energy sources (mandated by state law) on the New England electric grid, and opportunities for on-site distributed solar generation. Electric utilities are required to increase the proportion of renewable energy sources in their portfolios by 2% per year. The Roadmap increases that to 3% annually from 2025 until 2029.

What is the Opt-In Specialized Code?

Building codes set minimum standards for new construction, renovations, additions, and repairs of commercial and residential buildings. The Massachusetts Building Code consists of a series of international model codes and any state-specific amendments adopted by the Massachusetts Board of Building Regulations and Standards (BBRS).

When I had a porch rebuilt, my contractor had the plans reviewed by Belmont’s building inspector for code compliance. The building inspector then visited after construction to certify the work met code. When a plumber or electrician does work in your home, they are required to follow the plumbing and electrical codes. Similarly, there is a Building Energy Code that sets minimum standards for energy efficiency, called the Base Energy Code.

In 2009, the BBRS created an “opt-in” enhanced energy code known as the Stretch Energy Code or simply the Stretch Code. Communities voluntarily adopt the Stretch Code through approval by town meeting or city council. To date, 300 of the 351 Massachusetts cities and towns have adopted the Stretch Code, including Belmont (2011).

An updated version of the Stretch Code went into effect on January 1, 2023, and applies to new commercial and residential buildings as well as major renovations and additions. Note that once a community adopts the Stretch Code, it automatically is subject to future stretch code changes. Thus, the updated Stretch Code automatically applies to Belmont.

The Massachusetts Energy Building Codes apply to both commercial and residential buildings.

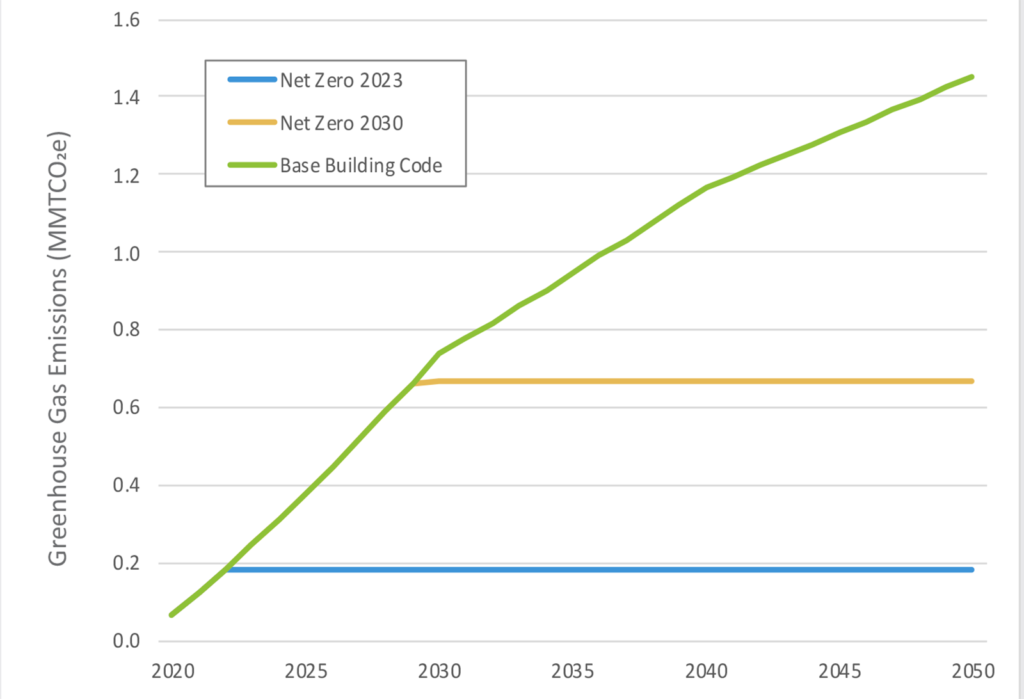

Future greenhouse gas emissions from new buildings in Massachusetts with and without a Net Zero code, from the Massachusetts 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap.

Measuring the Energy Efficiency of a Building

The Home Energy Rating System (HERS) Index is the industry standard to measure a home’s energy efficiency. It is a points-based system, performed by a third-party verifier, used to quantify overall energy use. The lower the HERS rating, the more energy efficient a home is.

The 2009 Stretch Code required all newly constructed houses to have a HERS Index rating of 60 for all-electric homes (e) and 55 for homes with fossil fuel infrastructure (ff). The updated Stretch Code (2023) requires HERS Index ratings of 55e/52ff. On July 1, 2024, the Stretch Code will require HERS Index ratings of 45e/42ff. Remember that a lower HERS Index indicates higher energy-efficient buildings. Thus, DOER required homes using fossil fuel to have a slightly higher level of energy efficiency than all-electric homes.

Beginning in July 2024, the required HERS Index for low-rise residential buildings for the Stretch Code and the Specialized Code will be the same, except the Specialized Code requires a more stringent HERS Index for houses greater than 4,000 square feet that are not all-electric.

The new Specialized Code applies only to new residential and commercial buildings, not renovations and additions.

The Specialized Code

The Specialized Code provides three pathways for developers to construct new low-rise residences:

All-Electric Pathway

For a house to be all-electric it must use air-source or ground-source heat pumps for space heating and cooling, a heat pump or solar thermal system for water heating, and electric appliances for cooking and drying clothes. A HERS Index rating of 45 or below is required or Passive House certification. If an all-electric house does not have rooftop solar, it must be “solar ready.”

Building under the Specialized Code using the All Electric Pathway is almost identical to building under the Stretch Code.

Mixed Fuel Pathway

A house with fossil fuel combustion for space heating, water heating, cooking, or clothes drying is considered a mixed fuel home and requires a HERS Index rating of 42 or below or passive house certification. A mixed-fuel home is also required to have a rooftop solar array, if feasible, to offset some of a home’s carbon emissions. By “feasible” a roof must be largely unshaded, receiving 70% or more of available solar radiation, annually.

Mixed-fuel homes must be “pre-wired” for the eventual conversion of all fossil fuel-powered appliances to electric. For example, if all the appliances are electric except for a gas range, there must be an electric outlet for an electric-powered range, and the electric load calculation must account for this future electric appliance.

Zero-Energy Pathway

This pathway applies to mixed-fuel, low-rise residences greater than 4,000 square feet, although any home that is zero energy would comply with the Specialized Code. Mixed-fuel houses greater than 4,000 square feet are not permitted to use the Mixed Fuel Pathway.

They are required to have a HERS Index rating of 42 without consideration of onsite solar production and a HERS 0 with on-site generation. A HERS Index of 0 means a home is producing the same amount of energy, on an annual basis, as consumed. A house would be HERS positive if it produced more energy than consumed.

What about commercial buildings?

The Specialized Code for commercial buildings maintains the same energy efficiency requirements as the underlying Stretch Code for all building categories except multifamily buildings. Multifamily buildings (residences greater than 12,000 square feet) must be Passive House certified.

For all other commercial buildings, the same three pathways available for low-rise residences to meet the Specialized Code apply: All-Electric; Mixed Fuels; and Zero Energy. Note that as with the low-rise residential code, the all-electric commercial pathway is the simplest to comply with, having essentially the same requirements as the Stretch Code.

All-electric buildings reduce carbon emissions, cost less to build, and improve health compared to mixed-fuel buildings.

Construction Cost

Studies have shown that constructing an all-electric building is less expensive compared to new mixed-fuel buildings that have electric systems plus fossil fuel combustion appliances. This makes intuitive sense since all-electric buildings have a single energy system while mixed-fuel buildings need two.

Health

Burning a liquid or gas inside a building, especially if you have other options, seems unwise. A 2023 study by Stanford University researchers bore this out when it showed that relatively high levels of benzene, a known carcinogen, are emitted by all gas stoves. The researchers related their findings to higher rates of childhood asthma in homes with gas stoves compared to homes with electric stoves.

Spills, Leaks, and Methane Emissions

It’s not just burning fossil fuels that is the problem. Transporting liquid petroleum by ship, rail, or pipeline carries risks of polluting spills, but it is now clear that the production and transport of all fossil fuels, including natural gas, result in significant leaks of methane gas into the atmosphere. Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Atmospheric levels today are about two and a half times preindustrial levels, are increasing steadily, and account for 30% of the observed temperature rise.

Time to stop building fossil fuel homes

Allowing new construction with fossil fuel infrastructure is ill-advised from a climate and economic perspective. Most fossil fuel appliances will have to be converted to electric within the next two decades or sooner, if we are serious about meeting our decarbonization goals. It is less expensive to build all-electric houses from the start, making new construction truly the low-hanging fruit for electrification. In contrast, transitioning our large inventory of fossil-fuel-powered homes to the future all-electric economy is slow and more expensive.

Compliance with the Specialized Code for all types of low-rise residential buildings is a small step above the underlying Stretch Code except for mixed-fuel homes greater than 4,000 square feet, which must have sufficient on-site electric generation to be zero energy (HERS 0).

The Specialized Code and Belmont

On behalf of the Belmont Energy Committee, I placed an article to adopt the Specialized Code on Belmont’s Spring 2023 Town Meeting warrant. At the urging of the Select Board, I withdrew the article to give town staff more time to analyze and determine if adoption might result in any negative consequences for Belmont. The Select Board agreed to place the adoption of the Specialized Code on the Fall Town Meeting warrant in November 2023.

Massachusetts has allowed Belmont to move towards the electric economy of the future. It is now up to us to adopt the Specialized Code as we did when we opted in to the Stretch Code in 2011. Contact your Town Meeting members and let them know how you think they should vote.

Roger Wrubel is a member of the Belmont Energy Committee.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.