By Anne-Marie Lambert

Here in Belmont, we live on the edge of two large watersheds—the Mystic River watershed and the Charles River watershed. Understanding our role in these watersheds is more important than ever as storms in the Northeast grow more intense and more frequent, and as the rise in Atlantic Ocean sea levels starts to affect the underground water table.

The lack of alignment between our political maps and the topography of our watersheds can make it tricky to understand Belmont’s role. In the flat low-lying areas of town where there isn’t much gradient, waters flow in directions that may surprise you. Even up on Belmont Hill, unexpected flooding can occur due to a variety of factors, including the location of underground bedrock, clay, soil, sand, and water, the location of roads, buildings, and drain systems that channel stormwater, and the way soil erosion from increasingly large storms affects those channels.

The town has several efforts underway to understand and address both water pollution and flooding challenges. Several of them involve engagement with our downstream neighbors.

The Clean Water Act at Work in Belmont

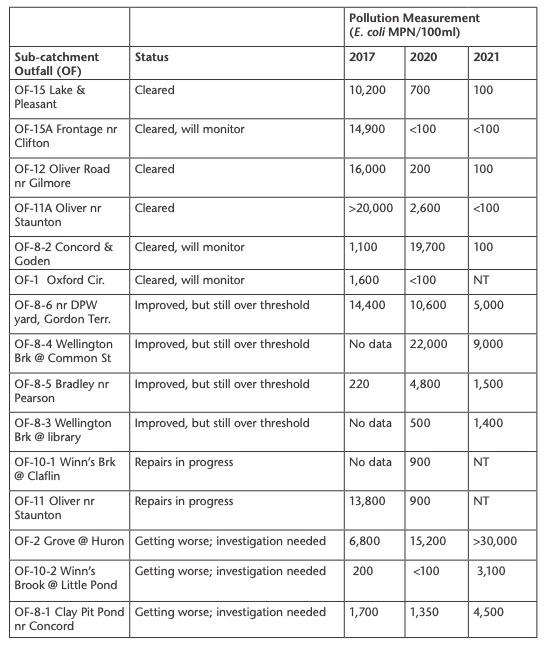

Belmont is in its fifth and final year of an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) consent order to clean up the sewage our aging sewer and drainage systems are putting into our waterways. The January 2022 biannual report showed that while the town has made a lot of progress, certain hot spots are likely to remain after EPA’s May 15, 2022, deadline to clean up all our pollution.

Many of the reporting requirements of this consent order will become required for all municipalities in June 2022 under the state’s new Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems regulations (MS4). Glenn Clancy, Belmont’s director of Community Development, is hopeful the EPA will be amenable to Belmont transitioning from the 2017 consent order to the new MS4 permit without needing to extend the consent order to a sixth year. At press time, he was working with the town’s contractor Stantec to prepare a summary of all the sewer and stormwater repair work the town has done over the last five years.

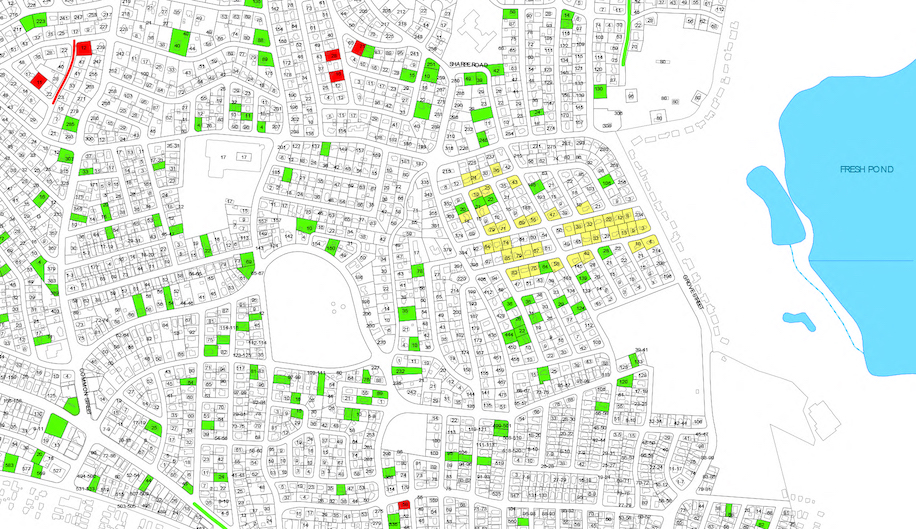

Details of Belmont’s January 2022 compliance report map showing the repairs done to address illicit connections to the storm drain system (red properties).

The town continues to try to clear sources of pollution from the edges of the storm drain system before tackling sources closer to our ponds and brooks. Wellington Brook outlet 8-6 (on the edge of the drain system by the Department of Public Works [DPW] yard) is an example of one of Clancy’s biggest frustrations. After significant upstream repair work in 2020, this outlet ran clear. Then, pollution spiked up again in December 2021. This spike could be due to the intermittent nature of pollution measurements (i.e., the timing of last year’s measurements missed a problem), or it could be due to a brand new failure in our 100-year-old sewer system. This outlet flows into subcatchment 8-4, which flows into subcatchment 8-3 and 8-1 in sequence. Measurements downstream can also be affected by whether there is dilution from cleaner tributaries in the drain system.

Moreover, weather can play a role in interpreting test results year to year. Dry weather in the week or two prior to a measurement can concentrate any pollution, and wet weather in the week or two prior can raise the groundwater table and explain unexpected moisture in the system.

Mixed results in areas where Belmont has repaired or relined sewer lines (source: January 2022 compliance report from Stantec).

ND: samples, none detected.

NT: not tested.

Sewer lining and laterals

The town has done a lot of work to line sewer laterals and mains. This work is funded by an MWRA I/I loan for a contract that will end soon. Clancy is working with Stantec to conduct a sewer system evaluation survey (SSES) to include wet weather flow monitoring under the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) infiltration and inflow program.

The town has spent $120,612 of the $1,348,208 approved in a Private Sector Sump Pump Removal & Sewer System Rehabilitation Construction contract. The cost to line a sewer line is $100 per linear foot for sewer lines and $150 per linear foot for drains. Typically, a lateral line from a sewer to a home is five to six feet, and a section of a main line under the street is about 20 feet. In addition to construction associated with lining sewers and storm drains, this contract also redirects any private sump pump discharges from the sewer to the storm drain system, where they belong.

The data above show where the town has found illegal connections of household wastewater to the storm drain system. These connections have all been addressed over the last five years, but there may be more. In order to find these connections, town contractors first isolate the problem to a single neighborhood block by measuring unexpected pollution in the drain system. They then need to enter each home on a block to perform dye testing to find the culprit. Progress during the pandemic has been slowed as homeowners have been more hesitant to allow town contractors to enter.

Clancy has taken advantage of the home entry required for a water meter replacement program in order to observe whether a basement bathroom or sump pump was visible. He found 17 locations where the existence of a basement bathroom might explain downstream pollution in the drain system. These findings allow town contractors to prioritize where dye testing might be most valuable.

Municipal Vulnerability Program Grants

Belmont has started work on the Stormwater Flood Reduction and Climate Resilience Capital Improvement Plan reported in the January/February 2022 Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter (“Belmont Awarded Climate Change Grant”). This project included field visits to 11 sites already prone to flooding to examine “topographical patterns, visible indications of current or past flooding, and catch basin and culvert conditions and characteristics.” The December field report concluded that “flooding in most of these areas is likely due to clogged catch basins, lack of catch basins in the road, and general topography of the area.”

All catch basins are cleaned annually in the spring, but some need more structural repairs than an annual cleaning can address. Some of the catch basins are clogged with invasive plants like knotweed which may require a system-wide solution. The town is developing a proposal to install additional catch basins, repair drains, and repair masonry associated with certain open drainage channels (e.g., for above-ground portions of Winn’s Brook).

These field visits, future field visits, and additional flow monitoring will provide flow data to an enhanced computer model of Belmont’s storm drain system which will predict areas most vulnerable to flooding with extreme storms.

In addition, the Municipal Vulnerability Program team has been interviewing community stakeholders in order to develop an action plan to address problem areas. The next step after this project will be to request construction funding for “green” mitigations such as rain gardens and other green infrastructure projects as well as “gray” stormwater infrastructure improvements (e.g., pipes, new catch basins, or wider culverts).

Meanwhile, the DPW FY23 budget includes a request for $800,000 for the Belmont portion of a project to mitigate the risk of flooding at the Beaver Brook culvert under Trapelo Road. This culvert is currently undersized for handling the full volume of the Beaver Brook cascade by the Mill Pond and Duck Pond in Belmont. Working with Waltham to widen the culvert would mitigate the risk of flooding this major roadway during big storms.

Spy Pond, Little Pond, and Little River

Most of Belmont is at the outer edge of the Alewife Brook portion of the Mystic River watershed or the outer edge of the Charles River watershed. Water flows downhill and toward the ocean in an obvious way. The main exception to this is a significant flow which starts in the hills of Arlington and flows into Spy Pond, then under Route 2 into Belmont’s Little Pond in a conduit that was built in the 1960s.

This flow passes through a corner of Belmont and then out to Little River and Alewife Brook in Cambridge. As far as I can tell from asking the Arlington and Belmont DPWs, the Spy Pond conduit is maintained by moving wooden planks on the Spy Pond side of the conduit and clearing debris seasonally. The conduit appears to be functioning well, but has not been inspected end to end for decades. Relatively few Belmont residents live near Little Pond and Little River— the Oliver Road neighborhood, Sandrick Road, and the Royal Belmont residences in Precinct 8, as well as the Hill Estates, now part of Precinct 1.

As described in the January/February 2022 BCF Newsletter (“Fifty Million Gallons of Sewage Released”), on rare occasions the Little River flows backwards a few days after an exceptionally large and long rainstorm starts. While diluted by rainwater, this backflow does carry pollution from the Cambridge and MWRA Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) to the Belmont neighborhoods around Little River and Little Pond.

The reverse flow is likely due to the combination of sedimentation reducing the capacity of Alewife Brook, high groundwater reducing the capacity of the soil to absorb water, and the “bounce back” of Mystic River flows to the low-lying areas of the Alewife Brook after they hit the Amelia Earhart Dam. Sedimentation is a long-standing process that results from soil erosion due to an increase in impervious surfaces in the watershed. As a result, Massachusetts rivers and brooks like the Alewife Brook are shallower than they used to be, reducing the volume of water they can carry during a storm.

Within the drain system in this area, major storms used to result in sewage and stormwater backups in the low-lying Winn’s Brook area. This has not been a problem since 2011, when the town installed a sewer storage and pumping station to retain a large portion of Belmont’s sewage underground and then pump it out when there was available capacity.

Department of Public Works director Jay Marcotte intends to explore ways to upgrade the “brains” of this system so that information about how frequently it is triggered can be made accessible remotely. Meanwhile, the system is exercised monthly and appears to have prevented the horrible sewage backups that used to reach into basements and bubble up through manholes.

Flooding from Below

During a severe rainstorm, areas prone to flooding can suffer flooding from both above and below. Rain soaks the soil from above, and a rising groundwater table soaks it from below as rain from the storm drains into the water table.

There is a second reason the groundwater table rises near a coast with rising sea levels like ours: groundwater is prevented from draining to the sea because salt water infiltrates further inland underground as the sea level rises.

As salt water rises and falls with the tides, it pushes the less dense freshwater inland at what engineers refer to as the “freshwater-saline water interface.” A similar “interface” underground is gradually moving further inland as the Atlantic sea level rises. Two hundred years ago, before all the dams were built, Alewife Brook used to rise and fall with the tides all the way from the Mystic River to Fresh Pond in Cambridge.

It would be difficult to model exactly where this interface is in the low-lying areas of Belmont during a particular storm. A recent study of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, concluded that almost half of storm flooding was likely due to groundwater table rising rather than marine tidal flooding. MIT researchers have also concluded this risk may be vastly underestimated, especially when it comes to underground utilities vulnerable to rising groundwater (see MIT’s website, “How rising groundwater-caused climate change could devastate coastal communities” at bit.ly/BCF-groundwater for stories of underground flooding in Saugus). Once our regional stormwater system is more accurately modeled, collaborating with our neighbors to invest in a model of a rising groundwater table could also help guide preparations for large storms.

Persistence Pays Off

With climate change, we need to be more diligent than ever about reducing pollution and understanding flood risks for ourselves and for our downstream neighbors. The town is working with Waltham to address Beaver Brook flood risks through the Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) program. The EPA’s enforcement of Clean Water Act regulations and additional MVP funding are both helping to reduce pollution and flood waters flowing downstream to Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville, and beyond via the Alewife Brook.

Improved computer models that reflect data from multiple municipalities in the watershed will help improve our understanding of what is likely to occur after future storms. Stormwater treatment features of the new library design will help mitigate downstream pollution and flood risks.

We’ve inherited fixed political boundaries that make it more challenging to study the flows and backflows above ground and underground and to understand who should do what next. I’m hopeful that we find more ways to cooperate with our watershed neighbors in order to make the Alewife Brook and Beaver Brook sub-watersheds clean and resilient as climate change progresses.

Explore: Pleasant/Lake Street Path

Walk the path between Pleasant Street and Lake Street along the Route 2 edge of Spy Pond to see pretty views of both Spy Pond and the culvert to Little Pond.

A short path behind the Royal Belmont residences on Acorn Park Drive leads through a beautiful forest to a great view of Little Pond. It is a public path owned by the state Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR).

Explore: 145 Brighton Street Path

This public access path has a pretty view of Little Pond and all its bird life. Owned by the DCR, this path leads to the downstream end of the large culvert containing Winn’s Brook. You can still see the posts of the old fishing pier.

Anne-Marie Lambert cofounded the Belmont Stormwater Working Group, a collaboration between Belmont Citizens Forum and Sustainable Belmont. She is a Precinct 2 Town Meeting Member and former Belmont Citizens Forum director.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.