By Joe Hibbard

Take a walk on the north side of the Great Meadow at the Lone Tree Hill Conservation Land and you might notice some recent changes in the landscape. A broad area along both sides of the Pitch Pine Trail, which was until recently an impenetrable thicket of invasive plants, is being cleared and on its way to a healthier forest/meadow edge landscape. The clearing is part of a long-term project to restore ecological balance to degraded landscapes that are part of the Lone Tree Hill Conservation Land. The project is led by the Land Management Committee for Lone Tree Hill and supported by the Judith K. Record Memorial Conservation Fund.

A key feature of the project is the removal and control of one particularly aggressive invasive species: glossy buckthorn. This species, native to Western Asia, Europe, and North Africa, is widespread throughout the property. Once known as Rhamnus frangula (renamed Frangula alnus), glossy buckthorn was introduced to New England in early colonial times. It is among the most temperature-hardy plants, able to survive winter lows of -20F to -35F. As recently as 1969, it was on the then-Arnold Arboretum Director Donald Wyman’s “general list of recommended plants” in his book Shrubs, and Vines for American Gardens. With little sensitivity at the time to its potential for ecological destructiveness, it was noted as “a vigorous shrub widely distributed by birds … easily grown in almost any soil.” A variety called Columnaris (Frangula alnus ‘Columnaris’), a popular hedge plant, was patented by the Cole Nursery Company in 1955.

Today, after decades of proliferation and successfully competing against native plants, glossy buckthorn is a severe nuisance and threat to natural areas throughout temperate North America. It is not uncommon to find it in pure stands where native plant communities have been all but eliminated. The species and all its varieties have been banned from import, propagation, and sale in Massachusetts.

Removal and control of invasive species like glossy buckthorn are important because these species can destroy native plant communities, resulting in an alarming decline in their ecosystem benefits, particularly their value as habitat for songbirds and other desirable animal and plant species. Invading species often arrest the natural processes of regeneration that allow our native plant communities to sustain themselves over time. In the absence of the natural controls that normally check the spread of these alien species in their home ranges, they are capable of outcompeting and displacing our biodiverse, centuries-old native plant communities.

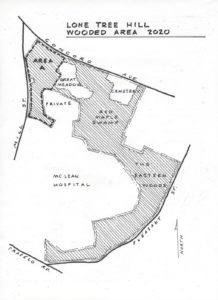

While glossy buckthorn has invaded nearly every corner of the Lone Tree Hill property, some of Lone Tree Hill’s diverse habitats are more vulnerable to invasion than others. For example, the Eastern Woods, a relatively large area above Pleasant Street extending up to the Belmont Day School and the McLean campus, is a relatively resistant patch of Appalachian oak forest that has an intact canopy of established trees characteristic of this forest type.

Having evolved relatively untouched for the past 90 to 100 years, the Eastern Woods reflects a recent history of minimal human interference. It is a young forest, but its canopy trees, woody understory, and herbaceous ground layer plants combine to create a setting that has proven fairly resistant to invasion by alien species. A few colonies of invasive species can be found in the Eastern Woods, particularly around its edges and at openings in the tree canopy where sunlight is more abundant and invites invasion from adjacent areas. The interior of the woods is, however, a reasonably intact community of native plants that naturally associate with one another.

Another fairly stable forest patch located at the interior of the Lone Tree Hill property is a wetland forest (referred to as the Red Maple Swamp), which contains mostly red maple and hickory canopy trees, and an understory of native highbush blueberry and maple leaf viburnum. Some of the larger hickory trees with trunk diameters up to three feet are impressive. This wetland forest, while not as free of invasive species as the Eastern Woods, has some interior areas that are relatively pristine.

Since shade suppression is a key factor in minimizing the spread of many invasive species, the healthiest parts of the Red Maple Swamp have a closed canopy that admits very little sunlight to the forest floor, limiting colonization by many invasive species. On the other hand, some of the Red Maple Swamp’s upland perimeter areas with a more open canopy are heavily infested. Lone Tree Hill’s chief invader, the glossy buckthorn, is reasonably shade tolerant and is particularly fond of wet sites. Glossy buckthorn has become well established in the Red Maple Swamp perimeter, and it seems only a matter of time before it populates the interior woods in greater numbers than it already has.

Outside of the Eastern Woodland and Red Maple Swamp, nearly all the other plant communities at Lone Tree Hill are somewhat younger, less ecologically stable, and more vulnerable to being overrun by invasive species. Many of them already support robust colonies of glossy buckthorn. This is principally due to the abundance of sunlight in these areas now or in the recent past, and the competitive advantages of the buckthorn.

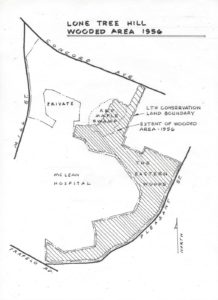

A 1956 USGS topographic map shows the Eastern Woods and part of the Red Maple Swamp as the only wooded areas on the then McLean Hospital property bounded by Concord Avenue, Pleasant Street, Trapelo Road, and Mill Street. The rest of the property was open fields with a scattering of tree clusters. These former open areas now include successional woods and the pitch pine woodland located in the northern corner of the property; the Mill Street edge; the edges of the Highland Meadow Cemetery; the perimeter of the Vernal Pool; and the Great Meadow itself. It is in these former open fields and younger plant communities, particularly those in the northern corner of the property, that the Land Management Committee’s efforts to control invasive species have begun.

The invasive species control project began in 2019 (See “Lone Tree Hill Restoration Shows Strong Start”). Before the recent clearing effort, A1 had some of the densest populations of glossy buckthorn on the property. It is a former meadow and orchard area that ceased being grazed or mown in the decades following the Second World War. Subsequently, it was colonized by several early succession native plants such as gray dogwood, gray birch, and staghorn sumac along with some canopy trees such as wild black cherry, oaks, and hickories. However, the abandonment of the pastures and orchards also offered an opening for glossy buckthorn, which by that time had established itself in the ornamental nursery trade and was producing annual crops of berries for birds to disseminate through the countryside. Thus, glossy buckthorn was able to become the dominant species in open areas like A1.

With about three and a half acres of buckthorn clearing accomplished so far in Area A1 and adjacent areas A7 and A9, the fruits of this labor can be seen by those who look carefully. Previously suppressed native wildflower species, sedges, shrubs, and tree saplings are visible in the ground layer plants, having been released from the smothering effects of the buckthorn.

The immediate plan for the next steps in Area A is to continue with annual follow-up suppression of buckthorn in the treated areas and to expand the removal work in the most heavily degraded areas contiguous to the pilot project area.

The Land Management Committee has made an excellent start to the control of invasive plants at Lone Tree Hill. Belmont owes this volunteer committee its thanks and future support.

Joe Hibbard is a landscape architect and Belmont resident.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.