By David Meshoulam

When I first tell people that I work in the field of “urban forestry” they look at me funny. “Urban areas have forests?” they ask. “I thought forests were out in the country.”

But urban forestry is a real thing. Over the past several years, its importance has become increasingly recognized as a critical component of a city’s infrastructure, and rightfully so! Trees create more livable and healthy communities by cleaning and cooling our air, mitigating against flooding, and improving the mental and physical health of residents.

In an era of climate change, with hotter summers leading to more health risks, especially for vulnerable communities, trees are a critical tool for improving peoples’ lives. Many of these benefits are real and measurable, providing cities and towns nationwide with billions of dollars of ecosystem and health benefits annually through cooler air, stormwater capture, and air pollution removal. Urban trees have also been shown to reduce blood pressure, improve mental states, and reduce levels of violence. The US Forest Services has created a series of online tools, called i-Tree (www.itreetools.org/), to quantify these benefits.

Consider a medium-sized red oak tree in front of a home. Using the i-Tree tool (mytree.itreetools.org/), a red oak with a diameter of 25 inches provides nearly $80 per year in ecosystem benefits. These benefits come mainly through energy use reduction by keeping the air cool in the summer and reducing cold wind infiltration in the winter, leading to reduced carbon emissions. The tree also absorbs carbon dioxide and other air pollutants and reduces stormwater runoff.

Trickier to measure, but equally important, are other co-benefits, like health care benefits, reduced anxiety, and increased property value. Multiply these benefits by the thousands of trees in a town, and the savings become significant. You can use i-Tree to figure out how much your local tree is worth too.

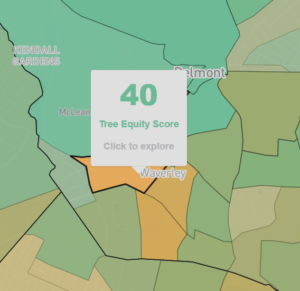

I-Tree isn’t the only tool to help guide local urban forestry efforts. My two favorites come from American Forests. The first is the Vibrant City Lab (www.vibrantcitieslab.com). The website provides a roadmap filled with articles and resources on how to think about, plan, and develop a model to help grow and sustain your community’s forest. The second is American Forests’ Tree Equity Score tool (treeequityscore.org/). This map provides census-level data on which areas in a town would most benefit from increased tree canopy. Each census block receives a “tree equity score” that factors in demographics and tree canopy coverage.

Locally, several funding streams and resources support tree preservation and growth in Massachusetts. For example, the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation has a division of Urban and Community Forestry (with one of its offices in Belmont near Beaver Brook!) and Massachusetts has one of the country’s oldest laws pertaining to public shade trees, with each municipality requiring a tree warden to plant, care for, and oversee the public trees in that community. Some towns, such as Belmont, even have a Shade Tree Committee.

Despite these supports, trees often do not receive the care and attention from residents that they deserve. That’s why many towns and cities have nonprofit organizations whose mission is to educate residents, plant trees, and advocate for increased resources for urban forestry. Some of these organizations are volunteer-led with small budgets while others are large staff-run organizations that receive significant grants and donations.

For the past half-decade, I have been involved in two such nonprofits. I sit on the board of Trees for Watertown, formed in 1985, and I am executive director of Speak for the Trees, Boston, which I cofounded in 2018. These organizations do important work in bringing people together to celebrate and care for trees, but their models are very different.

Trees for Watertown holds monthly board meetings and relies on the hard work of a committed group of volunteers to run its programs. Its activities include tabling at various events in the town, attending town council meetings, and assisting the town’s tree warden in educating residents about trees and tree care. It recently ran a summer program called Teens for Trees.

Trees for Watertown also plays a key role in ensuring that the town commits resources to its forestry operations and advocates for increased funding and is currently engaged in forming a new ordinance for the town. Because the organization is volunteer-run, it relies on small donations from residents.

Speak for the Trees, on the other hand, is a staff-run organization with several programs including tree giveaways, tree plantings, community and student education, educational webinars, and a summer program called Teen Urban Tree Corps. It works closely with researchers and students in Boston-area universities to run projects that analyze the relationship between trees, people, and the environment, and also with local neighborhood groups and organizations. Due to its large scope and substantial budget, Speak for the Trees actively raises funds from foundations, corporations, and individuals.

Considering the importance of urban forestry, Belmont residents might want to consider exploring how to support their urban forest. There are four open spots on the Shade Tree Committee, and an opportunity to jump into something that is already up and running. Or perhaps there’s interest in forming a working group or even a nonprofit organization? If so, residents will find many similar organizations across the area, not just in Watertown and Boston, but also in Arlington, Somerville, and Medford, among others, who are doing work in this arena and are eager to share their stories of challenges and successes.

David Meshoulam, PhD, is cofounder and executive director of Speak For the Trees, a nonprofit in Boston that seeks to increase the size, health, and equity of Boston’s urban forest, focusing on under-canopied neighborhoods by protecting existing trees and empowering residents to plant new trees in their communities.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.