By Roger Wrubel

It began for me in 1995. I was working with a new grassroots organization, the McLean Open Space Alliance (MOSA), that formed to try to protect more than 200 acres of undeveloped land owned by McLean Hospital. The hospital campus occupied about 50 acres, and McLean owned about 180 additional acres of forests and meadow beyond that. During a period when hospital finances were challenging, Partners HealthCare, of which McLean was a part, wanted to sell its “surplus” property to developers.

This created great controversy in Belmont. About a third of the town favored development, including the Board of Selectmen at the time, as a way to increase tax revenue, while a third opposed development, viewing the loss of open space as unacceptable. An intense four-year battle resulted in a compromise solution with some development and about 120 acres protected by a conservation restriction.

In my research for MOSA, I came upon an academic paper that described a large expanse of land in our area, including the McLean property, that had escaped development. Some parts had been pastureland acquired around hospitals that settled in the area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Examples included:

- McLean, established in 1894 and the only one of the hospitals still operating;

- Metropolitan State Hospital opened 1929, closed in 1992;

- Middlesex County Hospital, opened in the 1930s, closed in 2001;

- Fernald Developmental Center, opened 1888, closed in 2014.

Other properties had belonged to wealthy landowners whose estates found uses which spared them from commercial or residential development. These included:

- Mass Audubon’s Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary, formerly owned by the Atkins family in Belmont;

- The Waltham city-owned Robert Treat Paine Estate/Storer Conservation Land;

- Historic New England’s Lyman Estate;

- Cedar Hill Girl Scouts Camp and Waltham city-owned agricultural fields, both part of the Cornelia Warren estate in Waltham.

Linking these properties and several others by an off-road trail was still physically possible and would create a belt of publicly accessible open space which would include many natural and cultural features.

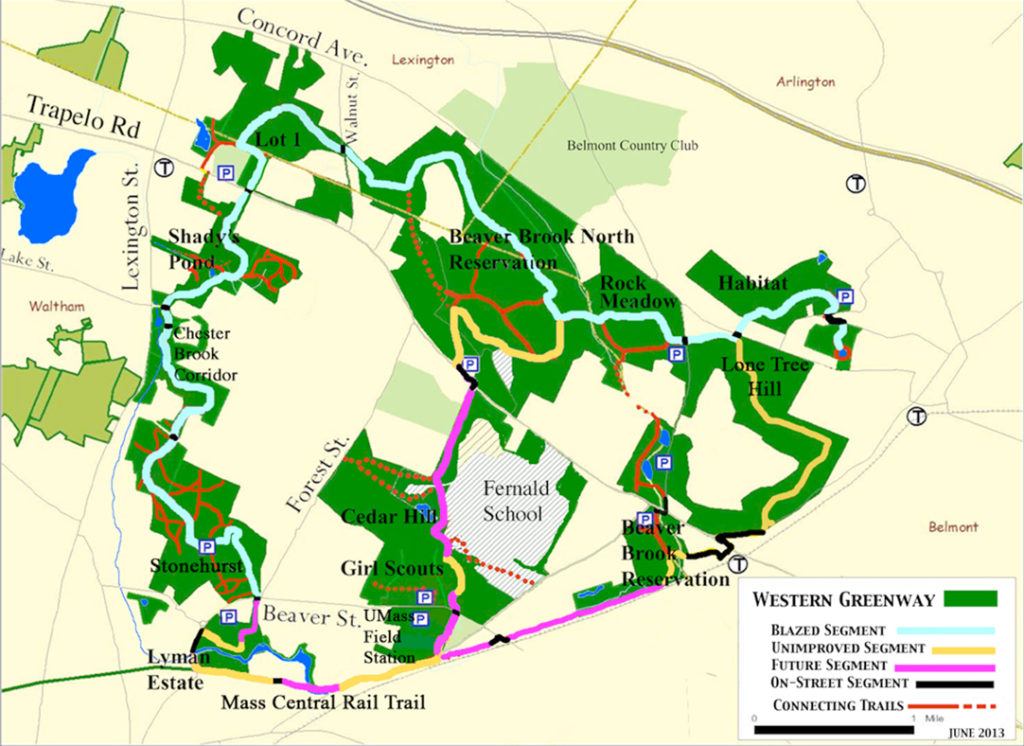

Working with a graphic artist, we created the first “Western Greenway” map, which showed the properties stretching across Waltham, Lexington, and Belmont, linked by a proposed “greenway trail” making a 12-mile loop. MOSA president Judy Record and I attended Belmont’s Town Day in 1996 using the map to engage passersby. We pointed out that the McLean open space had greater value than just that of the individual property because its loss would damage the larger greenway, i.e., the whole would be greater than the sum of the parts.

To me, protecting the greenway was important for two primary reasons. First, having a large continuous expanse of undeveloped “natural” land in our densely developed region of the state provided a unique, local recreational experience. Second, it was extremely valuable habitat for wildlife. Most of our protected lands are now islands in a sea of development. Small isolated patches of habitat are much less useful to a diversity of wildlife than larger uninterrupted habitats. In conservation biology, bigger is better.

The map generated a lot of excitement and curiosity. People were fascinated to learn that there was so much open space in and around Belmont. Many were familiar with Habitat, McLean, or Rock Meadow, but most had no knowledge of the Met State property, the lands beyond, and how they were connected. People pored over the map and we signed up many new MOSA members.

In 2000, I became sanctuary director of Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary and began leading walks through the “greenway.” My first walk attracted 35 people, including many local leaders. There was clearly pent-up interest in learning more about our nearby open spaces and how they were linked.

I soon discovered that I was not the only one thinking about a greenway. Land advocates in Lexington and Waltham were well aware of the value of these open spaces in their communities. What I brought to the table was the ability to look across town boundaries. In 2001, representatives of the Waltham Land Trust (WLT), the Citizens of Lexington for Conservation (CLC), Mass Audubon, and the Belmont Citizens Forum met and created an umbrella organization, Friends of the Western Greenway (FoWG), to work on making the Western Greenway a reality.

But what does calling someplace a greenway mean? As one WLT member, Marie Daly, said. “The greenway designation doesn’t create legal restrictions. It’s a planning tool the communities can use to draw attention to these vital areas.” (Globe NorthWest, March 27, 2003). The Western Greenway is made up of many properties: some publicly owned, some private, some protected from development, others not. The Western Greenway would exist if people thought and acted as if it were a real thing.

To accomplish this, we needed to get more people out using the greenway and thinking about it not as separate parcels but as a connected greenspace. As a start, FoWG—through the WLT—received funding from the Greenways Grant Program of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management to publish a brochure entitled The Western Greenway: An Opportunity to Link the Lands. That brochure named and described the greenway with a map and proposed trail. At the same time, we began to blaze the existing trails and make plans for what we needed to do to make the proposed greenway trail a reality.

The first evidence of political success in getting recognition for the Western Greenway came at a Lexington Planning Board meeting in 2005. A developer had bought part of the former Middlesex County Hospital in Waltham and Lexington at an auction of surplus state property. Greenway advocates let the Planning Board know that a section of the greenway trail went through that property and that we wanted the developer to do something to maintain trail access. The Planning Board acknowledged the greenway as a valuable regional amenity and included in its approval a requirement that the developer provide a greenway access trail between two of the house lots.

Western Greenway advocates became very busy in 2004 when the state legislature at the urging of the Romney administration slipped a provision into the state budget allowing for “fast- track” disposal of surplus state property. Several large abandoned hospitals were quickly auctioned off for development. The Middlesex County Hospital parcel, discussed in the previous paragraph, was another example. The state then scheduled an auction for the remaining 47 acres of hospital property, which was part of the Western Greenway, shown on the hospital parcel map as “Lot 1.”

It would take an entire article or more to describe the frantic, persistent efforts FoWG and all its underlying organizations made to prevent Lot 1 from being lost.

Starting in 2004, many meetings with our state representatives, a letter-writing campaign to the state’s legislative leaders, certification of five vernal pools in Lot 1, and letters to newspapers led to the auction being canceled and the eventual sunsetting of the fast-track surplus property disposal law in 2006. In 2008, Lot 1 was transferred to the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and joined to the Beaver Brook North Reservation.

In 2001, there were trails on some of the properties including Habitat, Lone Tree Hill, Rock Meadow, Met State (now the Beaver Brook North Reservation), and the Paine Estate. But there were many gaps to fill in the proposed Western Greenway Trail. We spent the next 13 years obtaining easements for new trails crossing the properties of the Waltham School Department, the Waltham YMCA, the Bishops Forest Condominium Associations, DCR, and the city of Waltham (kudos to Marc Rudnick and the WLT). Conservation commission approvals had to be obtained for each bridge and boardwalk constructed. Grants were written to pay for the building materials.

Mike Tabaczynski, Lexington resident, a member of the New England Mountain Bike Association, and a well-known New England Trail builder, laid out all of the new trails, supervised much of the work, and got other NEMBA members to join our workdays. All new trails, boardwalks, and bridges were built by volunteers. During the week we would put out a call for volunteers. Luckily there was a critical mass of folks who thought it was good fun to spend a summer day getting dirty, sweaty, and very tired building trails. (Of course, we did provide a pizza lunch.) An entire summer of work days was spent building a 500-foot boardwalk across the marsh on the west side of the former Met State property connecting to Lot 1. Several summers were spent building the Chester Brook Corridor, the part of the trail that parallels Lexington Street in Waltham between Lot 1 and the Paine Estate.

Filling in these gaps created a seven-mile Western Greenway Trail that runs from Habitat on the northeast to the Robert Treat Paine Estate on the southwest. You can now find the Western Greenway Trail in Google Maps!

FoWG continues to work maintaining the trail. For example, the WLT provided training and tools to groups of volunteers to oversee segments of the Chester Brook Corridor. We are also planning to fill in the last gap. In 2018, we obtained permission from Bentley University to cross a short section of woods on their campus that ends at the Lyman Estate. That trail segment remains to be built.

We have been in discussions with Historic New England about an exciting idea—building a bridge across a small creek that separates the Lyman Estate from the soon-to-be-constructed Mass Central Rail Trail sections in Waltham and Belmont. You can now walk the abandoned railroad tracks, which were cleared (thank you, Laurel Carpenter!) of the covering forest, east to Belmont or west to Route 128. (Warning: there are two rickety bridges along the way to Belmont that will be replaced or repaired when the rail trail is built in the near future.)

After a generation, our group of trail-builder/advocates have learned that persistence is required and pays off. It is hard to describe the pleasure of showing friends and family a trail you have helped build. In our region, it is a sweet time for creating a network of off-road trails that offer us an alternative for recreation, commuting, or just doing our shopping away from the ever-present automobile. Other completed or in-the-works trails include the aforementioned Mass Central Rail Trail from Cambridge to Northampton, the well-used Minuteman Commuter Trail, the Bay Circuit Trail from Plum Island to Duxbury, MA, Across Lexington, the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail from Lowell to Framingham, and the Watertown-Fresh Pond Bikeway.

Think about the sheer space that we give up to the automobile: roads, parking spaces, parking lots, rooms in our houses. The first argument against any development project is “too much traffic.” In Belmont, many believe their lives are being ruined by something called “cut-through traffic.” It’s time we take back our streets and homes from these mechanical tyrants. Don’t feel guilty—build trails and use them.

Completed boardwalk through the Western Greenway on former Metropolitan State hospital land. Photo courtesy of Roger Wrubel.

Roger Wrubel is the former sanctuary director of Mass Audubon’s Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary in Belmont.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.