By Anne-Marie Lambert

If only the 504 gallons of household wastewater which had been pouring into Wellington Brook and Winn’s Brook through underground culverts every day had been more visible, perhaps we as a town would have addressed the necessary repairs more urgently. That’s what Belmont did when a student noticed an oil spill leaking into Clay Pit Pond during a freeze on December 12, 2003. A ruptured return line to the underground storage tank at Mary Lee Burbank Elementary school travelled through the town’s storm drain system carrying 1,000 gallons of oil to Clay Pit Pond. Alerted to the spill, the town immediately called in an oil removal crew that worked through the night, suctioning oil from the pond’s surface and removing oil from the elementary school oil tank to allow for repairs. The town was fined $8,000 by the EPA, which concluded that the town responded quickly and effectively to the spill, minimizing the environmental impacts of the oil contamination.

With our leaking sewage, however, we have deliberately spaced out the painstaking detective work needed to find the sources of household wastewater silently polluting our brooks over several years, and waited to bundle repair work into consolidated contracts season by season.

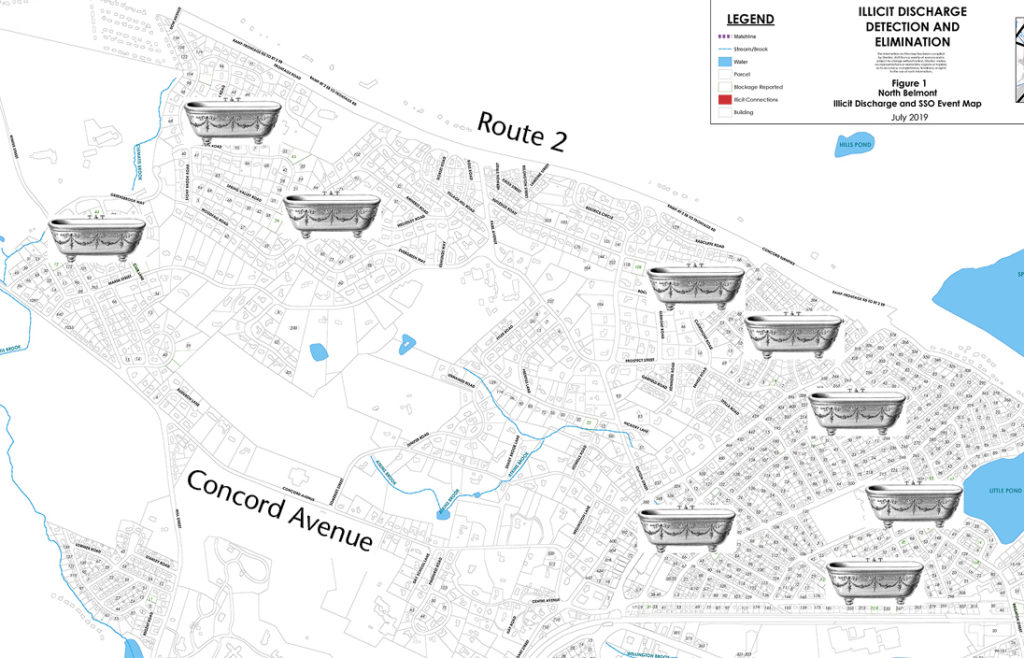

Detail of map titled “Illicit discharge detection and elimination” from Belmont’s Report On Compliance for the six months ending July 31, 2019. Bathtubs indicate neighborhoods with two or more blockages or illicit sewer connections. Image: Stantec

The town is under a 2017 federal consent order which requires the municipality to submit compliance reports to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) every six months. According to the town’s July 31 report, Belmont stopped 504 gallons of sewage per day (GPD)from reaching our brooks and ponds by:

- 210 GPD redirected from Wellington Brook by correcting one illicit connection on Bow Road

- 84 GPD redirected from Wellington Brook by lining the aging sewer laterals to two homes on Randolph Street

- 210 GPD redirected from Winn’s Brook by correcting one illicit connection on Brighton Street

According to the town’s July 31 report, this year the town has redirected 504 gallons—or more than six 80-gallon bathtubs—of sewage from Belmont’s brooks and ponds to the Deer island treatment plant.

This brings to 1,260 GPD the total wastewater stopped from entering the system since the 2017 federal consent order:

- 504 GPD removed between January and July 2019

- 126 GPD removed between June 2018 and January 2019 (see “Painstaking Progress,” May/June 2019 BCF Newsletter.)

- 603 GPD removed between January and June 2018 (see “Sewer Repairs In Progress” September/October 2018 BCF Newsletter.)

- Between June 2017 and January 2018, the town did baseline sampling and some detective work to find problems, but no repair work to remove wastewater (see “Finding Sewer Leaks Means Detective Work” March/April 2018 BCF Newsletter.)

The EPA requires any problems to be fixed within 60 days of obtaining definitive evidence. It’s not clear whether this provides incentive to space out the official definitive detection of problems that are expensive to fix.

Regardless, here are some problems identified in the July 31 report as likely to get addressed this year:

- Reline about 1,776 linear feet of aging sewer laterals

- Replace 4,376 linear feet of aging sewer laterals

- Continue to investigate source of pollution detected under Maple Street

- Consider whether to reline sewers under Bartlett Avenue to prevent contamination of the stormwater drains under heavy rain conditions

- Inspect basement plumbing at certain sites on Hoitt Road and Westlund Road as part of investigating remaining pollution coming from under Hoitt Road

- Dye-test drains under Hill Road/Brighton Road

- Rehabilitate sewer under Oliver Road and under Knox Street/Bellington Street neighborhood.

Some of these repairs are at sites where repair work was done last year, but subsequent pollution measurements in the downstream drains indicated there may be more work to do. The measurements may be picking up yet another illegal connection, or, in some cases, the measurement might just have picked up evidence of a dog owner making an illegal deposit in a stormwater drain upstream. Whatever the source, once the pollution is underground, out of sight, there can be a long wait before the E. coli and its source are detected.

Fifty years ago, the computing power in my pocket—and a lot of will power—got us to the moon. Today, we live in an age of remote sensors and automated models for making complicated decisions quickly. These innovative technologies have been very useful to address much more complex systems like autonomous automobiles and weather systems. I wish we were as impatient to address our water pollution as the space program was to get to the moon. Surely we could be using better and faster technology than our noses and laborious sampling and analysis of E. coli to detect pollution.

If we can install smart meters to monitor electricity use at every home, why can’t we put remotely accessible “stink-meters” in the drain system and flowmeters in the sewer system? Is it so hard for an automated analysis of the drain system to aggregate sensor data and get to likely pollution sources faster and more systematically? What are the hidden barriers to addressing more than a handful of problems every six months?

Anne-Marie Lambert is a former director of the Belmont Citizens Forum.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.