By Will Brownsberger

This winter’s storms have dramatized flooding in Boston and many other coastal areas. Is Belmont at risk? Despite climate change and rising sea levels, Belmont has minimal risk of direct seawater flooding in the next 50 years. The greatest threat to Belmont residents is the fragility of our regional infrastructure.

In the next five decades, scientists and planners predict a rise in sea level of as much as three feet. Stronger sustained winds in storms are also likely to produce greater storm surge. We will also see heavier rains. A detailed model of how water may move during storms in Greater Boston has been developed through a collaboration of state and local agencies and academics and consultants. Their assessment of changing risks should guide our planning.

Freshwater flooding at Blair Pond due to heavy rain. (Allegra Mujica photo)

Holding Back the Surge

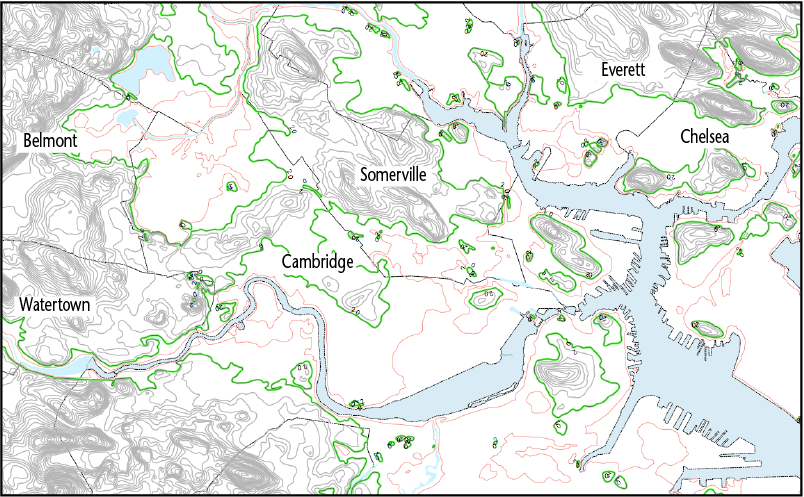

In the biggest storms so far, the storm surge in Boston Harbor has reached a level of about 10 feet above sea level, with sea level defined as roughly the mid-tide level. The map below shows that a few parts of the Winn Brook neighborhood are below the 10-foot level.

While Winn Brook residents have long experienced local fresh-water flooding during heavy rainfall, they are at low risk of salt-water flooding despite their low elevation. Unlike the low-lying areas in South Boston, the low-lying areas of Winn Brook are protected by the Amelia Earhart dam at the mouth of the Mystic River. The dam is effectively a seawall. It controls the water level in the Mystic basin, which includes Little Pond. Huge pumps keep the river from rising much even when extreme rains coincide with a high storm tide.

For Belmont, the hard question is how storm surge in the harbor will interact with the Amelia Earhart. Can the pumps keep up if water overtops the seawall? What if there has been heavy rain, and flood waters are coursing down the Mystic to meet the storm surge?

The short answer from millions of dollars of modeling is, “The ocean always wins.” If the sea outflanks or rises above the Amelia Earhart, we can’t do much. The pumps won’t remotely keep up with the flow. The ocean always wins in another sense—it dominates flow models even in the heaviest rain scenarios. Rain creates only very modest additional risk. So, the main question is how frequently, and for how long, the Amelia Earhart dam will be flanked or overtopped by storm surge, and how much damage can we expect from the overflow?

High tide at the Amelia Earhart seawall in March 2018. Note the water is much higher on the ocean side (right) than on the river side. (David Burson photo)

March 2018 saltwater flooding at the Schrafft’s City Center outside the seawall. (Bryan Gammons photo)

It appears that the Amelia Earhart will be flanked before it is overtopped. Low-lying areas immediately around the seawall create pathways for water to enter. Risks of flanking the seawall are estimated to reach the 1% level by 2045.

Adding berms and other structures in those pathways may lower risks and buy a decade or two, but they are not a 50-year solution. The city of Cambridge has funded some outstanding analysis that shows that the Arlington and Cambridge neighborhoods near Alewife will be at 20% annual risk of flooding by 2070. The at-risk zone will extend to the very lowest areas of Belmont, but most of the Winn Brook neighborhood appears to lie above the zone facing 1% modeled risk.

Every neighborhood in Belmont will face elevated risk of fresh-water flooding during heavy rains, but for the next 50 years, Belmont is relatively safe from salt-water inundation. Even as time goes on and the risks grow, most of the town is more than 30 feet above sea level and thus well beyond meaningful inundation risk for at least a century.

State of the State

But Belmont is not an island. If the Red Line or the major Boston highway tunnels are flooded and cannot be quickly restored, the regional economy will suffer. Power, water, or sewage outages would create hardship for many in Belmont and the region.

The responsibility for making infrastructure resilient is not owned by any one agency. In Massachusetts, responsibility for infrastructure is especially fragmented. We have tended to fund infrastructure by creating more or less independent borrowing authorities—MassPort, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, the MBTA, MassDOT. Also, in comparison to other states, our municipal units cover very small geographic areas.

Governor Baker is accepting more responsibility than past administrations for driving a statewide resiliency-planning process. In September 2016, the governor issued Executive Order 569 which requires the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs to:

. . . within two years of this Order, publish a Climate Adaptation Plan that includes a statewide adaptation strategy incorporating: (i) observed and projected climate trends based on the best available data, including but not limited to, extreme weather events, drought, coastal and inland flooding, sea level rise and increased storm surge; . . . within one year of this Order, establish a framework for each Executive Office to assess its and its agencies’ vulnerability to climate change and extreme weather events, and to identify adaptation options for its and its agencies’ assets.

This is the right idea and in keeping with legislation I got passed in 2013 but which was never fully implemented. The near-term challenge will be to complete this process in a serious way. The long-term challenge will be to sustain focus and make the necessary investments. Many smaller projects have clear value: Gaps in land barriers need to be filled, tunnel entrances protected, vent structures elevated.

Red lines are the 10-foot-above-sea-level contours and green lines are the 20-foot contours. (Map created by the author using Cartographica combining municipal boundaries from the U.S. Census via MassGIS and other data layers from MassGIS with elevation contours from the U.S.G.S. — The U.S.G.S. contours are derived from the National Elevation Dataset.)

Looking to 2030 and 2070

Some agencies are further along than others in understanding the risks. MassDOT really got the regional conversation started by investing in modeling to understand the exposures of the central artery and tunnel system. The MBTA is further back; it has begun to think about the problem but has not begun an asset-by-asset determination of its exposures. I’m particularly anxious to see clear plans in place to protect the Red Line at Alewife and the Green Line in Back Bay.

We have a little time, and we can pace the investment, but we need to sustain the work. Every major project in the coming decades should be designed to reduce risk as well as improve service. Each agency must have the resources necessary to build and retain institutional knowledge of its own challenges. The engineers and operators who work outside every day need to be insulated from the corrosive pressure of annual cost-cutting; they have knowledge that needs to be fed into the analytic inventories of problems. Once the inventories are complete, the staff must continue the risk-reduction effort.

There is an explicit consensus among planners in our region to focus on risks on two horizons: 2030 and 2070—near and medium term. The implicit consensus is not to look further. That is a reasonable choice.

If we don’t kick our global fossil-fuel habit, seas will rise much higher and the coast will recede, inundating many great cities and rendering centuries of human planning and labor obsolete. But we should not plan on the doomsday scenario yet. A lot will happen over the coming decades that we cannot anticipate.

As far as we can responsibly presume to see, climate change is something we can prepare for. In the longer term, we have to hope to succeed in technological innovation and collective action that brings climate change under control. We need to simultaneously prepare for climate change and work to minimize it.

Will Brownsberger is a Belmont resident and the state senator since 2012 from the Second Suffolk and Middlesex District, which includes Belmont, Watertown, and parts of Allston, Brighton, Fenway-Kenmore, and Back Bay.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.