By Sarah Howard with Patricia Loheed

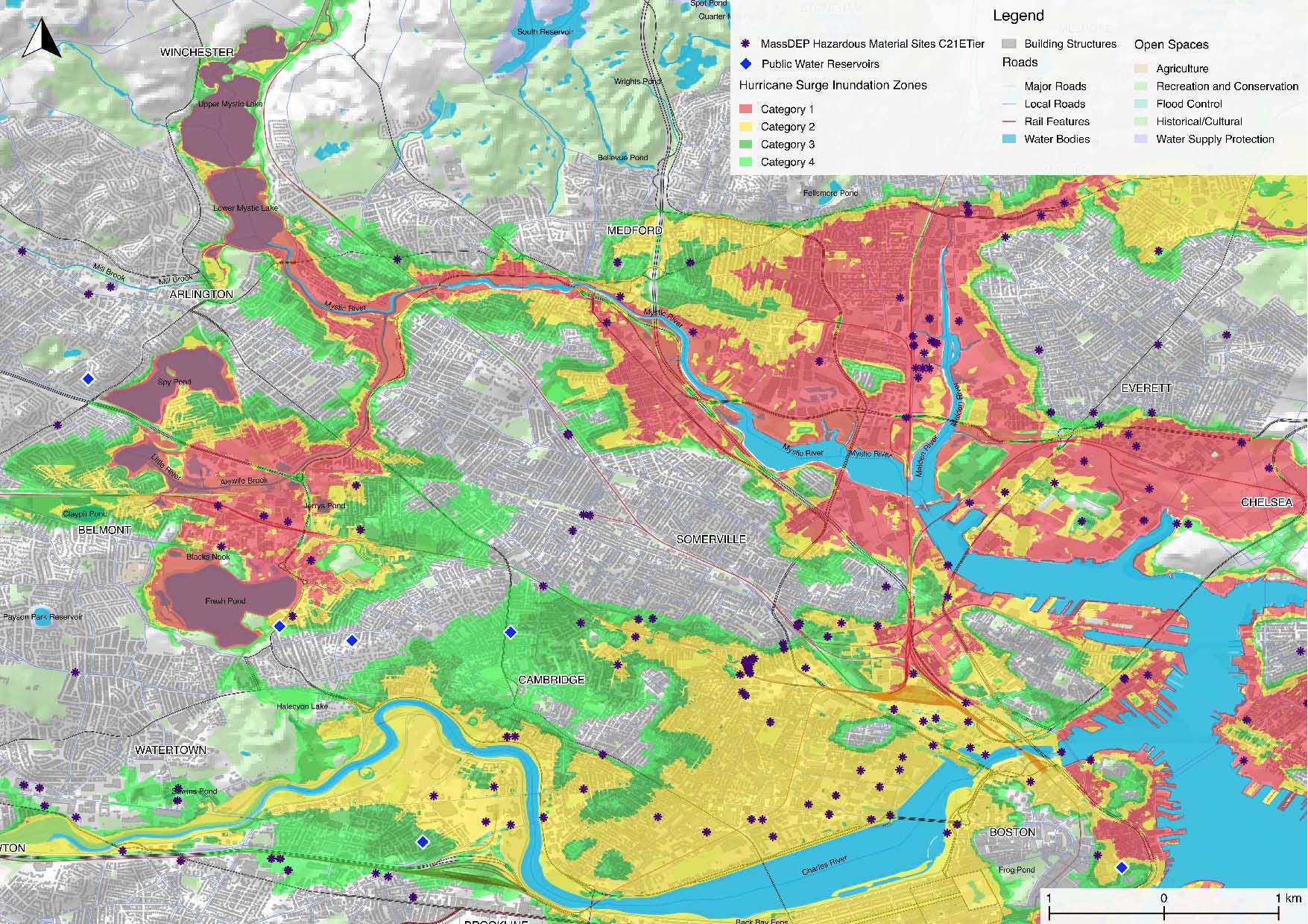

Map of inundation zones for hurricane surges. Red areas are expected to flood during Category 1 hurricanes; yellow, in Category 2 hurricanes; green, in Category 3 hurricanes. The data sources for this analysis include FEMA-NFHL identified flood zones (National Floor Hazard Layer), Categories 1 to 4; NOAA data from Surging Seas system; Mass DEP Hazardous Material Sites, C21E Tier. (Earthos map, authored by Miary Rasoanaivo with Philip Loheed)

“When it comes to natural disasters, 2017 was one for the record books,” according to a recent Weather Channel video. With increasingly extreme weather, area residents have been expressing concerns about the Alewife Corridor. Many still remember when a section of Route 16 remained underwater for two weeks in 1997, becoming impassable to traffic and blocking an evacuation route. The recent “bombogenesis” storm in early January, which caused significant flooding and storm surges in the Boston area, has only added to the commonly voiced concerns.

Most of us know the Alewife Corridor area as a transit corridor, with the MBTA Alewife Station as a visible landmark. Some know it as a walkable greenway, with occasional sightings of herons and otters. Not so visibly, it is a major utility corridor for gas, sewer, drinking water, and communications. But it is also a floodplain vulnerable to storm surges and flooding. In January, the Earthos Institute and Tufts University hosted the Alewife Corridor Collaborative Resilience Symposium to discuss the Corridor’s future. The 250 attendees included local residents, municipal staff, university researchers, members of local citizen groups, state representatives, and officials from the six adjacent municipalities of Belmont, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville, Medford, and Winchester.

Alewife Brook, alongside Route 16, at banks-full stage after the March 2, 2018, storm. This area

is a major utility corridor for gas, sewer, drinking water, and communications.

Questions ranged from elementary to complex. What is the Alewife Corridor? Why should we care about it? Why is resilience important? How do we build resilience in the corridor while recognizing our differences and geographic boundaries? What do we need to know; what do we need to do?

One speaker explained, “Resilience is ultimately about thriving for the long-term while being able to respond effectively to these types of challenges, and to catastrophic events.” To understand resilience in the Alewife Corridor, we need to understand the corridor itself. The Alewife Corridor is a geographic area that includes an urban river corridor, its floodplain and ponds, and six adjacent municipalities. It runs from the highlands of Belmont, Arlington, and Winchester to the Alewife Reservation in Cambridge, to the Alewife Brook and Alewife Parkway, to Medford, where it joins with the Aberjona and Mystic Rivers. In the past, the corridor has been protected from storm surges by the Mystic River’s Amelia Earhart Dam. Due to the corridor’s hydrology, location, density, and transportation and utility infrastructure, it is one of the most complex and vulnerable areas of the Boston region.

Despite significant stewardship efforts, this corridor remains troubled. Symposium participants explored its many challenges, like poor water quality; hazardous sites such as Jerry’s Pond located near water supplies like Fresh Pond; regular flooding and poor drainage; aged and threatened infrastructure, including utilities and dams; compromised biodiversity; and new development in the floodplain. These problems are becoming more complex as the ocean levels rise and as storms, storm surges, and flooding intensify.

During the two-day symposium, participants explored these problems. Many stated that one of the biggest challenges is governmental, not technical, since home rule leaves each municipality to follow its own preferences. The general sentiment was that solutions need to engage multiple communities and fulfill multiple purposes, such as improving housing, infrastructure, and open space, while increasing the corridor’s capacity to absorb and manage more water and remain functional during emergencies. The group offered several suggestions for future efforts:

- organize a group to look at the corridor as a whole, with representation from the adjacent towns;

- engage local universities and students to research the corridor and make their work available to towns and citizens;

- identify ways for towns and citizen groups to work together;

- look at funding for collaborative efforts and ways to include the state agencies;

- look at projects that would improve the corridor as a whole and would address utility issues; and

- find ways to model solutions to help adjacent towns (such as Belmont) work effectively with these uncertainties.

“It’s no longer about if [flooding] is going to happen, it’s about when and how. And no one knows precisely. So how do we make decisions together about our public and private investments as municipalities, as homeowners, as business owners?” said Philip Loheed, local architect and president of Earthos Institute. “We need ways to assess our decisions, to understand the risks and benefits of how we decide to build our roads, our utilities, our schools, how we decide to work with the water. How can we build our communities, and yet reduce our risks? How can we optimize the positive things happening in the corridor, today and and for our children? There is a lot of potential for good things here.” As for Belmont, as Jim Newman, resilience expert and Alewife Corridor resident, noted, “For the cities and towns in the Alewife watershed, there are huge benefits to working together. Belmont has the opportunity to build on the work by other towns to make life better for Belmont residents.”

Sarah Howard, LEED AP, is executive director of Earthos. Patricia Loheed is a founding board member of Earthos and past head of the Boston Architectural College School of Landscape Architecture.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.