By Mark Jarzombek

It comes as a surprise to people who assume that Boston’s colonization began with the settlement of Boston in 1630 that there was an equally important settlement in Watertown that same year. It was organized by Sir Richard Saltonstall, along with approximately 40 families. Unlike the Bostonians, the group in Watertown consisted of ranchers and farmers living primarily in homesteads spread out over the rapidly deforested landscape.

Though Boston takes the glory when it comes to the history of New England, the relationship between a town and its farm and pastureland was critical to the settlers’ success. Horses, cows, sheep, and pigs required very large tracts of land. But the history of the transition of the land from Native Americans to colonists and then to national land is murky.

Local narratives emphasize the legitimacy of the transfer by mentioning purchase arrangements. For example, in 1638, by order of the General Court, Watertown paid the Pequossette—who controlled the upstream areas of the Charles River—the sum of 13 pounds, seven shillings, and sixpence for the land. The post office in Arlington features a visual representation of this transaction. The large mural in the main hall is entitled Purchase of Land and Modern Tilling of the Soil. By William C. Palmer, the 1938 mural depicts a soldier paying a Native American some silver coins for the land.

The mural Purchase of Land and Modern Tilling of the Soil at the Arlington, MA, post office. Photo: Daderot/ Wikimedia Commons

But this is mostly myth. One must set the stage. The smallpox and other diseases that swept through the area largely came from the north and were the consequence of Basque fishermen and other European contact beginning in the 1500s as the Basques plied the fishing grounds of Maine and Newfoundland. By the end of the 1620s, disease had reached this area, and it is estimated that 90% of the population along the coast had died.

The survivors had little choice. There were not enough warriors to defend the land from the newcomers, and selling land was a way Native Peoples could try to control the narrative. But it was too late once it was clear that the new arrivals were in an expansionary mode.

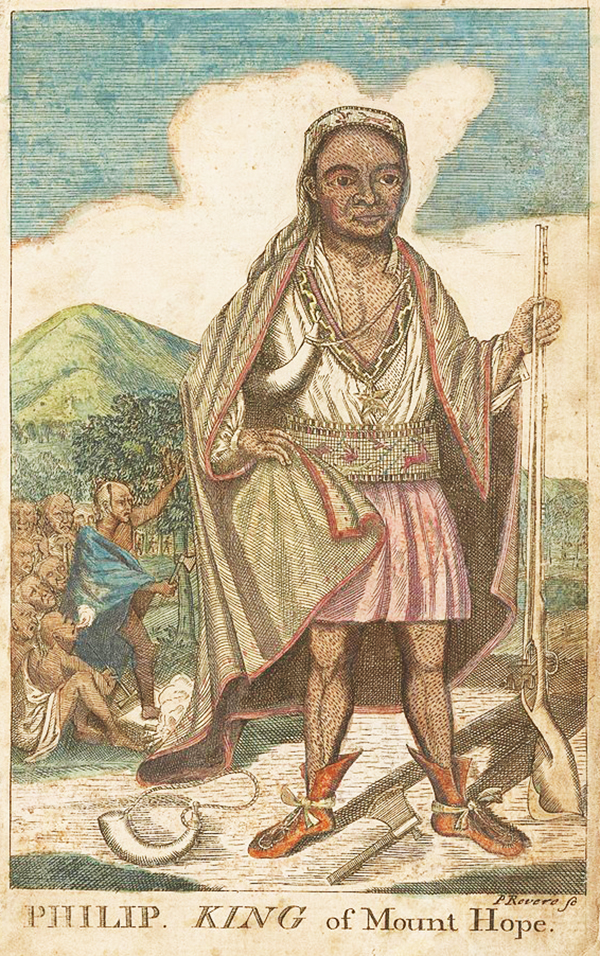

Some resistance did develop. The King Philip’s War (1675–1676) pitted the Indigenous peoples of the northeastern woodlands against the English New England colonies. The war is named for Metacomet, the Pokanoket chief and sachem of the Wampanoag, who adopted King Philip’s English name because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Plymouth Colony.

Metacomet (King Philip) from the 1772 The Entertaining History of King Philip’s War. Engraving: Paul Revere

The brutal war ended badly for the Native Americans. Families were separated, and some were sold as enslaved people and sent to Caribbean sugar plantations. The surviving refugees were forcibly clustered together in enclaves in Cape Cod and the islands.

The final blow, ironically, was the Massachusetts Act of Enfranchisement of 1869, which stated that Native Americans were “entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities, and subject to all the duties and liabilities” of citizenship. “All Indians,” the act decreed, “shall hereafter have the same rights as other citizens to take, hold, convey, and transmit real estate.”

What this really meant was that there was no longer any such thing as tribal territorial control in Massachusetts. To become a citizen of the state, the newly minted “Native American” had to become complicit in governmental structures that unraveled ancient bonds of community.

More importantly, what was left of tribal land could now be legally purchased. The area of Watertown, Belmont, and West Cambridge (as Belmont was then called) had been settled long before the Massachusetts Act of Enfranchisement. The Pequossette had, for all practical purposes, died out by the end of the 17th century along with the Mashauwomuk, who lived along the Mystic River just to the north.

Survivors, along with refugees from other local tribes, totaling a few hundred, were moved—among other places—to Nonantum Hill, a Christianized enclave in Newton, until that land, too, because of the Massachusetts Act of Enfranchisement, was bought out. The final traces of that Native American past were erased in the 1890s with the creation of the Newton Commonwealth Golf Course. Nonantum—as still marked on a map from 1700—was near the 15th hole, where the sacred spring still exists as a “water feature.”

This Nonantum—with not even a sign to register its location—has absolutely nothing to do with Nonantum, a region of Newton that was some two miles west, despite what Wikipedia claims. Nonantum, Newton, was named after a successful textile mill known as Nonantum Worsted Company, which was founded in the mid-19th century.

The local Native American world has been erased, appropriated, and historically misdirected. And that applies to the Belmont/Watertown area as well. When Pequossette Park was put up in 1929, it was not out of respect for the Pequossette but in anticipation of celebrating the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the Puritans in Boston in 1630. Back in the 17th century, the Pequossette used an area the original settlers called “a meadow”—now called Rock Meadow—that is a half-mile northwest of McLean Hospital and about 1.5 miles north of Pequossette Park. That “meadow” was one of countless such areas used by the Native Peoples for communal hunting and social gathering. By the mid-19th century, it had been converted into a farm and grazing land. In 1968, the town of Belmont purchased the property from McLean and the Belmont Conservation Commission assumed management, thus at least preserving some token of its ancestrality. But there is no indication on the site, nor even at Pequossette Park, about any of this.

“Indian” street and park names, here as elsewhere, were put in to make the colonial history more visible in the cultural landscape, especially for the arriving immigrants from Ireland, Russia, and Europe, who knew nothing about it all. In this way, the old guard could cement the place of colonial history in the broader history of the United States. So, for example, a plaque on the Old Powder House in Somerville reads: “The first occasion on which our patriotic forefathers in arms met to oppose the tyranny of King George III in 1775.” As the plaque points out, it was put up in 1892 by the Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the Revolution, a hereditary society formed in 1889 to promote awareness about the importance of the American Revolution.

These efforts were reinforced by the spread of colonial-style single-family houses that developed beginning in the 1880s, and that were sparked by the celebrations of the American Centennial in 1876. They became almost de rigueur across the region in the 1920s and 1930s. But apart from a few references to the Pequossette in this region, there is no acknowledgment —not even a plaque—that this land was once Native American.

One cannot turn back history, but one can—belatedly at least—begin to think of how to acknowledge the incontestable fact that the land we live on has a history more profound than just the history of colonial encounters.

Mark Jarzombek, PhD, is a history and theory of architecture professor at the MIT School of Architecture and Planning and a Belmont resident.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.