“If the fumes were purple, we’d have action a lot quicker. Because we can’t see them, we don’t realize they’re there.” So said Ania Camargo, a manager at Case Associates and a volunteer for Mothers Out Front, describing the plumes of methane gas leaking into the air all around Greater Boston, including 80 spots in Belmont.

“Gas companies began adding a ‘rotten egg’ smell decades ago, because methane is colorless and odorless,” says Camargo. “But apparently even that bad smell isn’t enough to spur corrective action. This is far more serious than people realize.”

She was addressing an April 21 meeting of concerned citizens from Belmont and surrounding towns sponsored by Mothers Out Front (MOF), whose mission is “Mobilizing for a Livable Climate.” “We’re appalled and concerned about what we’re doing as a society and what we’re leaving behind for our children,” Camargo added.

Gas leaks are a threat to health – they exacerbate asthma and other respiratory illnesses – and the methane they leak is 84 times more potent a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over a 20 year period, contributing to climate change.

But isn’t gas good?

Natural gas is the good fuel, right?

One of the major goals of MOF, a group with chapters in Massachusetts (including Belmont), New York, and Virginia, is to change that perception.

Unburned natural gas is mostly methane. According to a 2013 International Panel on Climate Change report, methane, during its first 20 years in the atmosphere, is 86% more potent than CO2 in trapping the heat that causes global warming. Yes, burning natural gas to cook or heat your home is better than burning oil or coal (it emits less CO2), but the unburned, leaking methane is adding to a poisonous environment at an alarming rate.

Where is the other 10%?

According to the natural gas industry itself, “a full 90% of all natural gas removed from the earth gets to the end user.” Thus: up to 10% is unaccounted for. While some of that is used to power compressor stations, the rest is leaking into the atmosphere and the soil. Dead or dying trees are one clue that gas pipes below may be leaking into the soil.

Leakage occurs at the source of extraction, along transmission pipes, and especially from aging underground pipes in urban and rural areas. National Grid, in a meeting with the Belmont Mothers Out Front chapter, stated that roughly half of Belmont’s natural gas pipes are cast iron or unprotected steel and were therefore leak-prone. The utility also said that most leaks occur—or expand—during the winter when frost heaves damage the aging pipes.

If natural gas/methane leaked at only 3%, it would tie with coal in a race for atmospheric toxicity. At 10%, it wins the (tarnished) gold medal by a mile.

Adding injury to injury.

It gets worse: we consumers pay for that lost methane. The gas companies charge for 100% of the amount they send by incorporating the unaccounted-for gas into customer rates. The recipients pay for that 100% but receive only 90%. So not only are we paying for their losses, we’re subsidizing our own poisoning. Camargo said, “If utilities had to pay for the losses, they would be out repairing the top ten percent of the largest leaks immediately.” MOF seeks to get the biggest leaks repaired promptly, change the 100%-for-90% billing practice, fight projects such as the Keystone Pipelines and any new fracking and fossil fuel infrastructure, and to promote alternative energies.

Legislation on Beacon Hill.

Two bills currently in the Massachusetts State House address parts of the issue. House bill 2870 seeks to protect consumers from paying for lost and “unaccounted-for” gas and electricity. House bill 2871 (and a similar Senate bill, S1767) mandates that gas companies check for gas leaks when roads with gas pipes are dug up, and fix any leaks found within 12 months. (The bills are backed by 32 cities and towns, but Belmont has not yet signed on.)

State Senator for Massachusetts’s 2nd Suffolk and Middlesex District Will Brownsberger, a Belmont resident and former selectman, said, “Hopefully we’ll be able to make progress on gas leaks as part of the omnibus energy bill. Lots of Members are in favor of moving forward. We need to give the gas companies reasons—financial incentives—to act faster on repairing the leaks.”

What’s the danger?

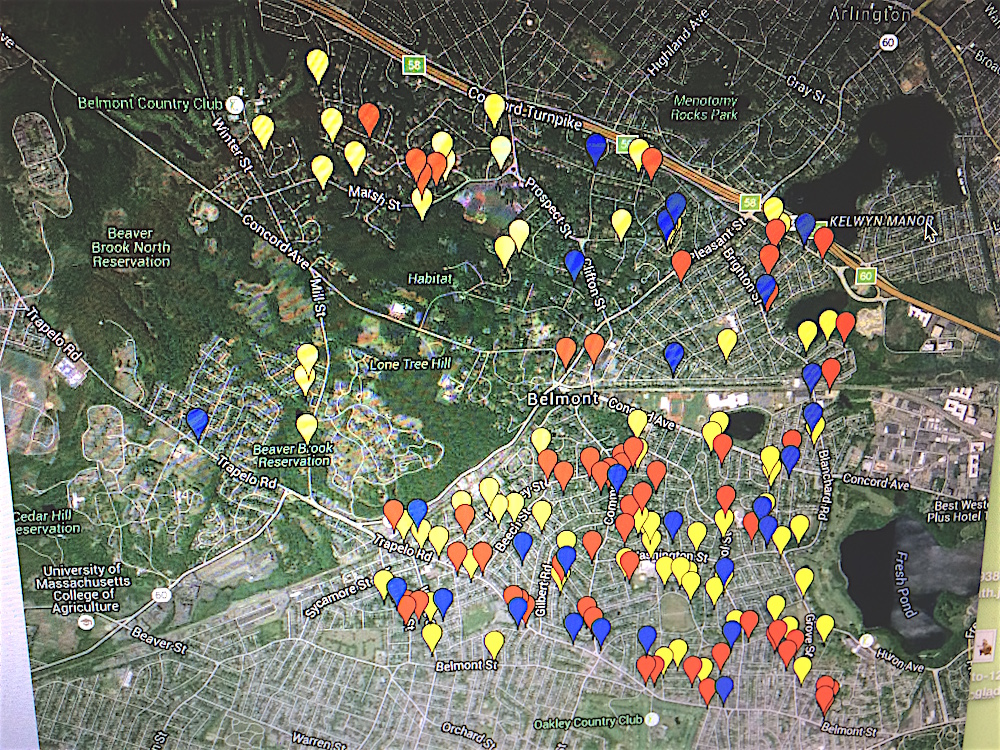

Boston University Professor of Earth and Environment Nathan Phillips has been studying such leaks around Greater Boston for several years. He estimates “there are about 3.9 leaks per mile throughout Greater Boston.” He and his team have mapped them. In Belmont, 80 unrepaired leaks have been identified by HEET in Belmont.

The majority of leaks in Belmont may or may not pose an imminent danger of explosion—but all of them do, in fact, contribute to a significant reduction in air quality. And, although not caused by leaky pipes buried underground, Ohlin Bakery’s recent sudden gas-induced explosion serves as a reminder that natural gas disasters can and do happen in Belmont.

Why aren’t more gas leaks repaired?

“There’s not a sense of urgency,” said Camargo as she walked the group through the three Massachusetts classifications of leaks:

- Grade 1. A leak that represents an existing or probable hazard to persons or property. Such a leak requires repair and continuous action until the conditions are no longer hazardous.

- Grade 2. A leak that is recognized as nonhazardous to persons or property at the time of detection, but justifies scheduled repair based on probable future hazard. Such leaks shall be repaired or cleared within 1 calendar year but no later than 15 months.

- Grade 3. A leak that is recognized as nonhazardous at the time of detection and can be reasonably expected to remain nonhazardous. Such leaks shall be reevaluated during the next scheduled survey, or within 15 months of the date last evaluated, whichever occurs first, until the leak is eliminated or main replaced.

“Probable future hazard?. . .”

There is no mention of the size/volume difference between any grade of leak, location (such as “within 30 feet of a school”) or any definition of “immediate” repair in Grade 1. Grade 2 is a “probable future hazard,” but allows 12 to 15 months for repair. Grade 3 “is recognized as nonhazardous…” even though it’s methane, leaking into the air.

Town can’t force action.

Dan Fitzgibbon, DPW Permit Coordinator for Belmont, said, “We don’t get involved with the leaks directly. National Grid identifies and classifies them and if they’re rated “1,” they fix them immediately. We issue permits for road repairs and installations and underground repairs of pipes. In my six years here, we haven’t lost a house to an explosion, but we certainly want the leaks all cleaned up as soon as they can.” He said his office did not have the authority to override the gas companies’ classifications of leaks or to prioritize their actions.

Clearly, there’s work to be done.

According to Camargo, stopping methane leaks around the nation alone would do more to slow global warming than almost anything else. The recent cancellation of the Kinder Morgan pipeline project in New Hampshire and western Massachusetts was due to stiff political and consumer opposition and poor customer support. The burning of all fossil fuels contributes to the degradation of the atmosphere and the trapping of greenhouse gases that accelerate climate change.

There is no clean fossil fuel.

To learn more: H4222 http://1.usa.gov/1UzUQ https://malegislature.gov/Bills/189/House/H2870 https://malegislature.gov/Bills/189/House/H2871

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.