Cambridge Sewer Separation Makes Alewife Brook Cleaner

By Anne-Marie Lambert

On December 21, 2015, Cambridge celebrated a major milestone of the Alewife Sewer Separation project, a massive public works that separates sanitary sewers from storm sewers. When these two types of sewers are connected, heavy storms drive raw sewage into local waterways such as the Alewife Brook—as has been happening at the Brook for decades.

As of December 21, the city will now provide water quality treatment of stormwater runoff from more than 400 acres of the urbanized Huron Avenue and Fresh Pond neighborhoods by directing it to the 3.4-acre constructed wetland at Alewife before it enters Little River. The work was completed by removing a weir wall in an underground drainage vault at the Fresh Pond rotary after upstream sewers were separated.

This completed work will result in an 85% reduction of the annual combined sewage overflow (CSO) volume to Alewife Brook. In the past, many storms caused combined sewage and stormwater to flow directly into Alewife Brook at the CAM004/401A outfall. Now, during major storms, the only combined storm overflow water routed to Alewife Brook will come from the CAM401A part of the system (by Rindge Avenue). All other storm flows from the CAM004 area discharging into Alewife Brook have been separated from sanitary sewers. By design, during dry weather, some groundwater and remaining infiltration water leaking into the pipes from the ground will continue to flow and emerge at the CAM004/401A outfall.

The CAM004/401A outfall is located just behind the graffiti-decorated MBTA rotary parking garage by the Alewife bike path. It has represented the tiny beginning of Alewife Brook ever since a portion of Alewife Brook that once reached Fresh Pond was buried in a conduit in the 1940s. The 72-inch Alewife Brook Conduit was installed under Wheeler Street to reduce the stench of what used to be a ditch running between Little River and the rotary.

This wasn’t the first time Cambridge took action to address pollution concerns in this area. In 1873, the city built a small dam by today’s Fresh Pond rotary to protect the city’s water supply from 19th-century pollution coming from the increasingly stagnant “Great Marsh.” This pollution included combined sewage as well as direct waste from area tanneries, slaughterhouses, and roadside horse manure. At that time, Wheeler Street represented the boundary between Belmont and Cambridge.

The 1875 construction of tide gates on the Alewife Brook at Broadway Avenue in Somerville further restricted flow—and fishing—in this very flat area. With increasing concern about their public water supply, in 1880, Cambridge successfully petitioned to re-annex a portion of the new town of Belmont between Fresh Pond and Little River. Cambridge also experimented for 10 years with building a conduit to carry fresh water from Little Pond to Fresh Pond. Due to the poor water quality of this source, this practice was terminated. Fresh Pond was subsequently supplied with water drawn from Stony Brook and Hobbs Brook reservoirs.

It has taken 135 years to recognize and clean up pollution flowing from Cambridge and Somerville’s CSOs and other downstream sources into Alewife Brook, on to the Mystic River and, eventually, into Boston Harbor. A 1991 court order, later amended in 2001, mandated that three major projects be completed by December 2015 within the CAM004 area to eliminate the incidence of CSOs into Alewife Brook:

Combined sewer separation and new storm and sanitary trunk sewers along Fresh Pond Parkway (contract 2 A/B)

Combined sewer separation in CAM004 area near Huron Ave (contracts 8 and 9)

Stormwater wetland and conveyance pipeline (contract 12)

The amended court order also required numerous smaller downstream projects to reduce CSO discharges to practical limits within Cambridge and Somerville. These downstream projects have all been completed.

A Quarter-Century of Work

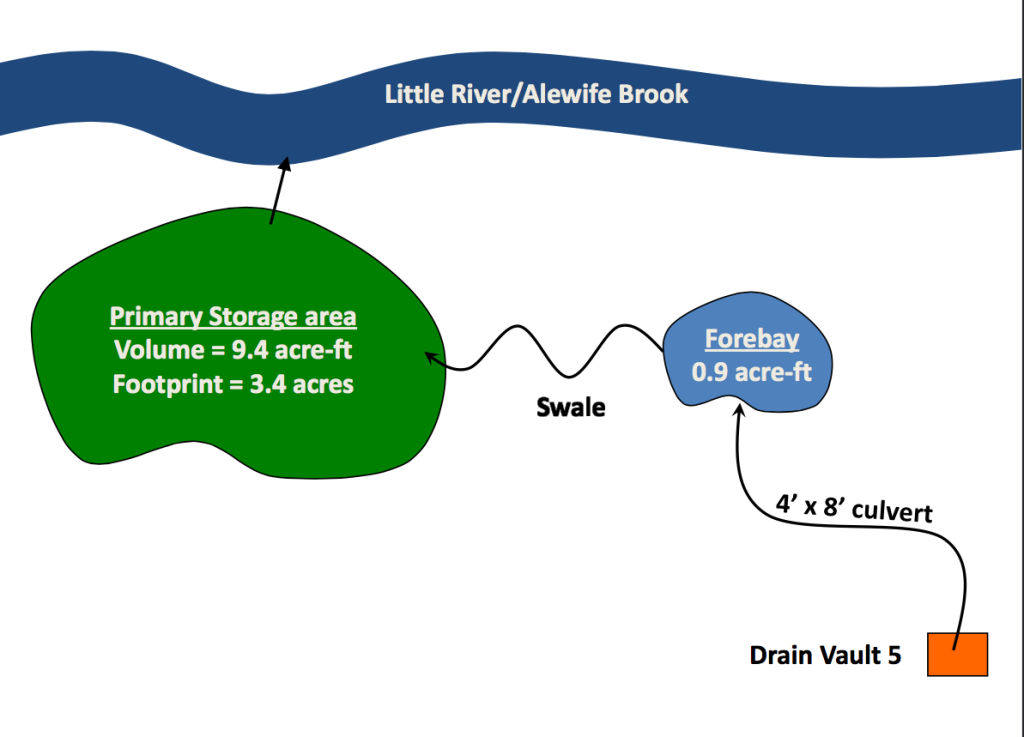

In September 2014, the Belmont Stormwater Working Group enjoyed a fascinating talk by Bill Pisano about the 25 years of adaptive planning and sustainable engineering required to address the court order. Now semi-retired, Pisano is a senior advisor at MWH, the engineering firm responsible for planning and designing much of the work for the city of Cambridge. He demonstrated how small “first flush” storm flows would be deflected to the new wetlands pond in Alewife Reservation for initial treatment by a special German bending weir that’s underground. He recounted the challenge of discovering that the underground MWRA sewer interceptors from Belmont were lower than advertised, requiring redesign of a new 4-by 8-foot stormwater culvert system which brought stormwater from the CAM004 area into the new wetland pond.

Pisano also explained how a 1997 project to reconstruct pipes under Fresh Pond Parkway from Huron Avenue to the Concord Rotary and along Wheeler Street included a clever adaptation of a tank-cleaning technology. A daily “flush wave” is created by routing the filtrate waste from the nearby Cambridge water treatment plant into a special chamber which, when filled, rapidly opens, creates a cleansing “flush wave.” This technology addressed the vulnerability of these pipes to clogging from “FOG” (fats + oil + grease) from local restaurants, which had previously filled almost half the sewer conduits under Fresh Pond Parkway. New public health regulations for restaurants now further reduce troublesome FOG in sewer pipes.

Today the 4-by 8-foot underground culvert conveys stormwater from a drainage vault under Concord Rotary, under Wheeler Street and west along Fawcett Street, and then under the tracks, ending at the wetlands just north of Cambridgepark Drive near the bike path. There, stormwater is routed through a forebay to capture sediment pollution, and then into a bioswale, which filters certain pollutants through carefully selected vegetation. The award-winning constructed wetlands opened as a park in October 2013 and started accepting stormwater from other Cambridge neighborhoods downstream of the CAM004 area soon afterwards. In addition to treating pollution, it serves as a popular park for residents of the many recent Alewife area developments.

Separating the stormwater infrastructure from the sewer system in the Huron Avenue neighborhood took years of incremental construction projects, some on the drainage system of individual homes. It disrupted traffic. Bill Pisano explained that, in addition to separating the underground infrastructure, it was shown to be economical for the city of Cambridge to fund “private property inflow (PPI) control” measures to find and reroute roof drains and sump pumps so they went into the stormwater system instead of the separated sewer system. This PPI plan required careful building inspections of more than 1,000 homes. The plan eliminated potential wet weather sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs) for extreme storm events.

It should be noted that the constructed wetlands where the newly separated stormwater is treated have been designed and sized for the purpose of treating pollution and as a flood control measure for storms up to a 10-year frequency. For more intense storms, a separate project at the MWR003 outfall helps “mitigate the potential for flooding in tributary community sewer systems by providing extreme storm system relief in conjunction with … the planned closing of nearby outfall CAM004,” according to the MWRA’s December 15, 2015, Quarterly Compliance and Progress Report to the Massachusetts District Court. The MWR003 project was substantially completed in October 2015, with the installation of an automated gate, an underflow baffle for floatables control, and a 48-inch siphon interconnection at Rindge Avenue. The automated weir gate and upgraded siphon interconnection enhance the sharing of flow between the parallel Alewife Brook Sewer and Alewife Brook Conduit.

Bill Pisano identified some key takeaways that could be utilized in other locations that are facing similar challenges to those overcome during the improvement of the CAM004 drainage area.

By adopting a more holistic approach to the design of infrastructure projects, sustainable engineering in the future will be able to take place more naturally and allow projects to reach their full potential in improving communities. This has been the direction of Cambridge’s efforts over the last 20 years. The CAM004 separation program—including the Alewife Stormwater Wetland—is the culmination of these efforts, and has quickly become a “gem” as it encompasses all aspects of this methodology.

Anne-Marie Lambert is a Director of the Belmont Citizens Forum.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.